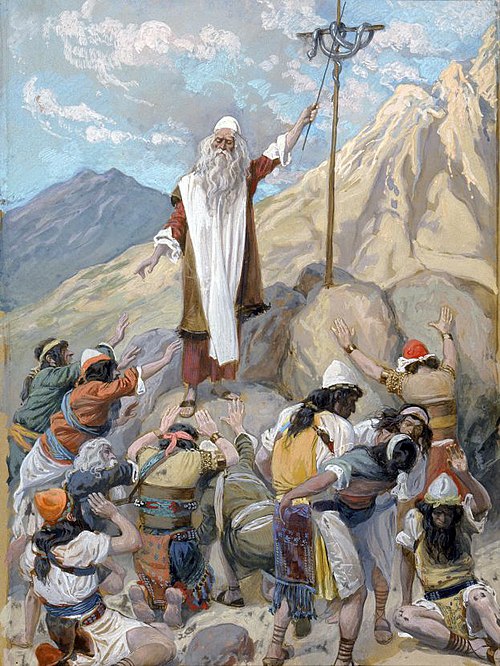

Numbers 21:5-9+

James Tissot)

BRAZEN SERPENT BECOMES

NEHUSHTAN A THING OF BRASS

The story of Nehushtan is both fascinating and instructive, unfolding across three distinct episodes spread over more than a thousand years, yet conveying timeless spiritual lessons that remain practical and relevant to our modern world. What began as a gracious provision from God eventually became an object of misplaced trust and devotion, illustrating how even divinely appointed means can be corrupted when they replace dependence on the living God. Because of its historical sweep, theological depth, and practical application, the Nehushtan narrative lends itself naturally to a compelling sermon or teaching on idolatry, spiritual drift, and the need for daily revival. Below are the three key biblical passages that frame this unfolding story, followed by notes and observations compiled from a variety of trusted sources, drawing together historical, theological, and practical insights. Enjoy!

THE TIME OF MOSES

Numbers 21:5-9+ The people spoke against God and Moses, “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we loathe this miserable food.” 6 The LORD sent fiery serpents among the people and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. 7 So the people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned, because we have spoken against the LORD and you; intercede with the LORD, that He may remove the serpents from us.” And Moses interceded for the people. 8 Then the LORD said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent, and set it on a standard; and it shall come about, that everyone who is bitten, when he looks at it, he will live.” 9 And Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on the standard; and it came about, that if a serpent bit any man, when he looked to the bronze serpent, he lived.

THE TIME OF HEZEKIAH

2 Kings 18:1-4+ Now it came about in the third year of Hoshea, the son of Elah king of Israel, that Hezekiah the son of Ahaz king of Judah became king. 2 He was twenty-five years old when he became king, and he reigned twenty-nine years in Jerusalem; and his mother’s name was Abi the daughter of Zechariah. 3 He did right in the sight of the LORD, according to all that his father David had done. 4 He removed the high places and broke down the sacred pillars and cut down the Asherah. He also broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the sons of Israel burned incense to it; and it was called Nehushtan.

THE TIME OF JESUS

John 3:14-16+ “As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up; 15so that whoever believes will in Him have eternal life. 16 “For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life.

PROVISION, PERVERSION,

FULFILLMENT

As you can see, across Scripture spanning the Old and New Testaments, the account of the bronze serpent unfolds as a unified theological thread moving from provision, to perversion, to fulfillment. In Numbers 21:5–9, Israel sinned by grumbling against God, and the Lord judged them with fiery serpents, yet in mercy He provided a means of deliverance, commanding Moses to lift up a bronze serpent so that whoever looked in faith would live, salvation coming not from the object itself, but from trusting God’s word. Seven centuries later, in 2 Kings 18:1–4, the same bronze serpent had become an object of idolatry, burned incense to by the people, and King Hezekiah rightly destroyed it, naming it Nehushtan (“a thing of bronze”), because what once pointed to God had come to replace Him. Finally, in John 3:14–16, Jesus revealed the ultimate meaning of the symbol, declaring that just as the serpent was lifted up in the wilderness, so He Himself would be lifted up on the cross, so that whoever believes in Him would not perish but have eternal life, showing that the bronze serpent was never the source of life, but a foreshadowing of salvation by faith in the crucified and risen Son of God.

1508 Michelangelo's image on the ceiling

of the Sistine Chapel.

The brazen serpent—later contemptuously called Nehushtan by King Hezekiah—was originally a God-ordained instrument of healing in the wilderness (Nu 21:8–9), but over centuries it degenerated into an object of idolatrous worship, prompting Hezekiah to destroy it during his reforms (2 Ki 18:4). By naming it Nehushtan, meaning “a mere piece of bronze,” Hezekiah stripped away its false sanctity and exposed it for what it had become: not a sacred relic, but a man-made object wrongly revered. The episode illustrates how God’s genuine gifts, when detached from obedience and faith, can be corrupted into idols—often preserved by euphemisms that disguise sin rather than confront it. As Ancil Jenkins observed, relabeling wrongdoing does not change its nature, just as calling a tail a leg does not give a cow five legs. What once symbolized God’s mercy and judgment ultimately required destruction when it supplanted God Himself, even though it had also served as a profound type of Christ, who would later be “lifted up” to bear sin and bring true healing and life (Jn 3:14–15; 2 Cor 5:21).

The Brazen Serpent (Nehushtan)

The footnote in the New International Version at 2 Kings 18:4 is most interesting. When Hezekiah found the brazen serpent made by Moses in the wilderness still being worshipped, he destroyed it. The NIV says, “… he called it Nehushtan.” The footnotes explain the meaning—”a serpent made of brass.”

One is made to wonder how such an idol could have existed so long (ED: About 730 years! See Nu 21:8-9+). It would seem that in the reformation movements of one of the judges or kings, it would have been destroyed. My opinion is that it was not recognized as an idol and hence was preserved. Perhaps they justified it by not calling it an idol. Hezekiah, however, came and called it what it really was—a brass image of a snake.

How often we justify sin by calling it a different name! Some call adultery, “a meaningful relationship.” We excuse covetousness by calling it “prudence” or “economy.” A life of sensual pleasure is “living with gusto.”

In answer to a critic, Abraham Lincoln asked, “How many legs does a cow have?” “Four,” was the reply. “If you call her tail a leg, how many does she have? asked Lincoln. “Five,” was the answer. “No,” Lincoln said, “Just calling a tail a leg, doesn’t make it a leg.”

Have we made a similar mistake? Do we think that sin is not sin, just because we do not call it by its right name? Ancil Jenkins

ADDENDUM NOTES ON NEHUSHTAN - "mere piece of bronze" 2 Ki 18:4 something made of copper, the copper serpent of the Desert. Nehushtan the name given to a bronze snake Moses ordered to be made in the wilderness (Nu. 21:9+).

And Moses made a bronze (nechosheth) serpent (nahas/nachash) and set it on the standard; and it came about, that if a serpent (nahas/nachash) bit any man, when he looked to the bronze serpent (nahas/nachash), he lived.

NEHUSHTAN. The bronze (nechosheth) serpent (nahas/nachash) destroyed by King Hezekiah during his reform of the temple worship (2 Ki 18:4). It had been made by Moses centuries earlier. The name can mean “a piece of bronze” (NASB marg.), and it was probably so named by Hezekiah in contempt. K. R. Jones (The Bronze Serpent in the Israelite Cult) lists various archaeological discoveries which have demonstrated that in Mesopotamia before the time of Abraham the serpent was a common symbol of fertility and the return of life. Apparently it was the Hyksos who brought the serpent symbol into Palestine, where at least seven cultic bronze serpents have been found in excavations dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (1650–1200 b.c.).Representations of serpents together with fertility goddesses on plaques and cult standards were frequent in the ancient Near East.

NEHUSHTAN - see full article online Dictionary Of Deities And Demons In The Bible PAGE 615

NEHUSHTAN נחשׁתן I. The word nĕḥuštān occurs once in MT, in 2 Kgs 18:4, where it is the name of the bronze (or copper) serpent (nĕḥaš hannĕḥōšet) that →Moses had made in the wilderness (as related in Num 21:8–9) and that King Hezekiah destroyed. The word is a compound of *nuḥušt (Hebrew nĕḥōšet), ‘bronze, copper’, plus the *-ān affix (preserved as -ā- in Hebrew by dissimilation from the -o- type vowel in the previous syllable). The word nĕḥuštān literally means ‘the (specific) thing of bronze/copper’ (cf. the similar morphology of liwyātān, →Leviathan). Implicit in this name is a verbal play on nāḥāš, ‘snake’, of which nĕḥuštān is an image

Complete Biblical Library Nehushtan was the name that King Hezekiah gave to the bronze serpent Moses made in the wilderness (2 Ki. 18:4). Hezekiah destroyed the serpent, because the people had burned incense to it as an act of idolatrous worship. The name is derived from a play on the words nahas/nachash, "serpent," and nechōsheth, "bronze." This symbolism is not unique in the ancient Near East, though exactly what it represents is not clear. One can see that the snake in the desert was used in the course of healing (Nu. 21:4ff), a common motif found in a wide variety of cultures throughout the ages. The healing power of snakes was assumed because of their seeming immortality, the ability to shed their old skin. How this image functioned in Judean society at any juncture is not certain, aside from that it became an idol worshiped by the people.

Moses lifts up the brass snake stained glass

window at St Marks Church, GillinghamBRAZEN SERPENT - During the period of the wilderness wanderings, Israel murmured against the Lord. As a disciplinary measure, God sent “fiery serpents” among them (Nu 21:5–9+). May have been cobras, whose bite produced a burning fever. When the stricken people imploringly turned to Moses, he at the command of God made a brass (copper) serpent, no doubt a replica of the viper with the stinging, deadly bite which had already bitten them. One should not consider this as sympathetic magic, for it probably served as a symbolic reminder of the divine displeasure. Centuries later it became a rallying point for idolatrous worship in Israel which caused the godly Hezekiah to destroy it (2 Ki 18:4). Christ refers to it figuratively as a type of His own approaching death on the cross ("As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up; so that whoever believes will in Him have eternal life. " Jn 3:14-15+), as being “made sin for us” (2 Cor 5:21+) and as bearing our judgment.

Related Resource:

QUESTION - What was Nehushtan? - GotQuestions.org

ANSWER - The word Nehushtan occurs one time in the Bible, in 2 Kings 18:4, “He [Hezekiah] removed the high places and broke the pillars and cut down the Asherah. And he broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the people of Israel had made offerings to it (it was called Nehushtan).”

2 Kings 18:4 points back to Numbers 21:6–9, “Then the LORD sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. And the people came to Moses and said, ‘We have sinned, for we have spoken against the LORD and against you. Pray to the LORD, that he take away the serpents from us.’ So Moses prayed for the people. And the LORD said to Moses, ‘Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.’ So Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on a pole. And if a serpent bit anyone, he would look at the bronze serpent and live.”

In the time between Moses and Hezekiah, the Israelites began worshiping the “fiery serpent” Moses made out of bronze. It is only mentioned in connection with Hezekiah’s reforms, but the Nehushtan worship could have been taking place long before Hezekiah. While it is understandable how an item that brought miraculous healing could become an object of worship, it was still blatant disobedience to God’s commands (Exodus 20:4–5). The bronze serpent was God’s method of deliverance during the incident recorded in Number 21. There is no indication that God intended it to ever be used again.

Exodus 20:4-5 “You shall not make for yourself an idol, or any likeness of what is in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the water under the earth. 5 “You shall not worship them or serve them; for I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children, on the third and the fourth generations of those who hate Me,

While He does not refer to it as “Nehushtan,” Jesus does mention the bronze serpent in John 3:14, “As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up.” Just as anyone who was bitten by a serpent could be healed by looking to the bronze serpent Moses lifted up, so can anyone look to Jesus, who was lifted up on the cross, to be spiritually healed, delivered, and saved.

Interestingly, the word Nehushtan appears to simply mean “piece of brass.” Perhaps Hezekiah named it “Nehushtan” to remind people that it was only a piece of brass. It had no power in it. Even in the Numbers 21 incident, it was God who healed, not Nehushtan.

Nehushtan should be a powerful reminder to us all that even good things—and good people—can become idols in our lives. Our praise, worship, and adoration are to be directed to God alone. Nothing else, regardless of its amazing history, is worthy.

QUESTION - Why is a bronze serpent used to save the Israelites in Numbers 21:8-9? GOTQUESTIONS.ORG WATCH VIDEO

Monument of the bronze serpent on Mount Nebo

in front of the church of Saint Moses

ANSWER - Throughout the wilderness wanderings of the Israelites, God was constantly teaching them things about Himself and about their own sinfulness. He brought them into the wilderness, to the same mountain where He revealed Himself to Moses, so that He could instruct them in what He required of them. Shortly after the amazing events at Mt. Sinai, God brought them to the border of the Promised Land, but when the people heard the reports from the spies, their faith failed. They said that God could not overcome the giants in the land. As a result of this unbelief, God sent them into the wilderness to wander until that generation died out (Numbers 14:28-34).

In Numbers 21, the people again got discouraged, and in their unbelief they murmured against Moses for bringing them into the wilderness. They had already forgotten that it was their own sin that caused them to be there, and they tried to blame Moses for it. As a judgment against the people for their sin, God sent poisonous serpents into the camp, and people began to die. This showed the people that they were the ones in sin, and they came to Moses to confess that sin and ask for God’s mercy. When Moses prayed for the people, God instructed him to make a bronze serpent and put it on a pole so the people could be healed (Numbers 21:5-7).

God was teaching the people something about faith. It is totally illogical to think that looking at a bronze image could heal anyone from snakebite, but that is exactly what God told them to do. It took an act of faith in God’s plan for anyone to be healed, and the serpent on the stick was a reminder of their sin which brought about their suffering. There is no connection between this serpent and the serpent which Satan spoke through in the Garden of Eden. This serpent was symbolic of the serpents God used to chastise the people for their unbelief.

A couple of additional lessons are taught in the Bible regarding this bronze serpent. The people did get healed when they looked at the serpent, and the image was kept for many years. Many years later, when the Israelites were in the Promised Land, the serpent became an object of worship (2 Kings 18:4). This shows how easy it is for us to take the things of God and twist them into idolatry. We must never worship the tools or the people God chooses to use, but always bring the honor and glory to God alone.

The next reference we find in the Bible to this serpent is in John 3:14. Jesus indicated that this bronze serpent was a foreshadowing of Him. The serpent, a symbol of sin and judgment, was lifted up from the earth and put on a tree, which was a symbol of a curse (Galatians 3:13). The serpent lifted up and cursed symbolized Jesus, who takes away sin from everyone who would look to Him in faith, just like the Israelites had to look to the upraised symbol in the wilderness. Paul is reminding the Galatians that Jesus became a curse for us, although He was blameless and sinless—the spotless Lamb of God. “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21).

Chuck Smith: "What does it Mean When People Start Worshipping Relics or Idols?” A. They have lost their consciousness of God's presence. 1. In reality He is always there, "for in Him we live." "Where can I flee from thy presence?" - We are not always aware of Him. B. Somehow within we are trying to recapture that which was lost. 1. The day we felt God's presence and power. 2. That time when God's joy filled our lives. 3. How did we ever lose it? - The cares of this life; - the deceitfulness of riches, - the lust for other things.

Chuck Smith - Sermon Notes for 2 Kings 18:1-4 A THING OF BRASS

When people lose a living awareness of God’s presence,

they often cling to relics, places, traditions, or past experiencesSUMMARY - The history of the bronze serpent in Numbers 21 shows that Israel’s rebellion brought divine judgment, yet God graciously provided deliverance through a simple act of faith: those bitten were commanded to look at a bronze serpent lifted on a pole and live—not because the bronze was sacred, but because looking meant obedient submission to God’s authority. Jesus later identified this event as a type pointing to Himself, teaching that just as the serpent was lifted up, so He would be lifted up on the cross to bear the judgment for human sin, and all who look to Him in faith will live, even if they do not fully understand how such simple trust saves. Tragically, what began as a God-given means of grace became, centuries later, an object of idolatry; the preserved bronze serpent was worshiped until Hezekiah destroyed it, rightly calling it “Nehushtan”—a mere piece of bronze. This exposes a timeless danger: when people lose a living awareness of God’s presence, they often cling to relics, places, traditions, or past experiences in an attempt to recapture former spiritual reality. But objects, buildings, or memories are not sacred in themselves; they are only instruments God once used. Unless past encounters with God are carried forward into present obedience and faith, they become idols that hinder spiritual progress, and must be named for what they are—Nehushtan, nothing more than brass.

Unless past encounters with God are carried forward into present

obedience and faith, they become idols that hinder spiritual progress,

and must be named for what they are—Nehushtan, nothing more than brass.

I. THE HISTORY OF THE BRASS (Nu 21:6-9+)

A. The people were murmuring against God and rebelling against His authority.

1. The Lord sent serpents of fire into the camp and many were dying from their bites.

2. The Lord commanded Moses to make a serpent of brass and set it on a pole.

a. The people were commanded to look at the brass serpent if bitten.

b. There was nothing sacred about the brass.

c. by looking they were obeying God thus coming under His authority.

B. Jesus said: "and as Moses lifted up the serpent In the wilderness...." (Jn 3:14-16+)

1. The serpent was a type for sin.

a. Their sin of rebellion to God's authority.

2. Brass a symbol of judgment.

3. Jesus on the Cross took the guilt of our sin and received God's judgment against sin.

a. If we will just look to Jesus, we shall live.

b. They may not have understood how just by looking at the brass serpent could help. Lie there dying and refuse to look.

C. Somehow this brass relic was preserved 700 yr.

1. But the people were now worshipping it.

2. They were burning incense to it as though it were God.

3. Hezekiah when he came to - the throne broke it in pieces and said "Nehushten."

II. "WHAT DOES IT MEAN WHEN PEOPLE START WORSHIPPING RELICS OR IDOLS?"

A. They have lost their consciousness of God's presence.

1. In reality He is always there, "for in Him we live." "Where can I flee from thy presence?"

a. We are not always aware of Him.

B. Somehow within we are trying to recapture that which was lost.

1. The day we felt God's presence and power.

2. That time when God's joy filled our lives.

3. How did we ever lose it?

a. The cares of this life; the deceitfulness of riches, the lust for other things.

III. PEOPLE TODAY IN THEIR MINDS BURN INCENSE TO SACRED RELICS.

A. "You don't mean you are going to take the tent down?"

B. Maybe there is a certain spot.

1. While standing near this tall pine tree God spoke to you. You can remember now the joy.

2. They need to remove that tree now to build larger facilities.

3. The church's progress often stopped by foolish clauses.

C. Nehushtan, call it what it is, a thing of brass.

1. It's not a god.

2. It's not sacred or holy.

a. This tent is not a church.

b. Neither is the old chapel or the new sanctuary.

c. This tent is just canvas stretched over rope.

1. The church meets here.

2. When you're not here it's just an ugly old tent.

3. The experiences of the past are history and have no true value unless they have been transmitted into present realities.

a. "I wish we could stay in the tent". Nehushtan.

b. "Aren't you going to miss the tent?" Nehushtan.

"Forgetting those things which are behind and reaching for those things which are before I press for the prize of the high calling of God in Jesus Christ." (Phil 3:13-14)

Chuck Smith -2 Kings 18:4 (ED: "NEHUSHTAN THEOLOGY")

SUMMARY - This verse exposes Israel’s loss of consciousness of God, as the people clung to a once-God-given symbol to satisfy a spiritual hunger, resulting in confusion between means and object of worship. In response, Hezekiah took two decisive actions: he deliberately stripped the bronze serpent of its sacred aura by calling it Nehushtan—“a mere piece of brass”—and then destroyed it completely. The passage warns that God’s gifts, when detached from God Himself, can become spiritually harmful, as seen when people give reverence to buildings, liturgies, denominations, past experiences, or religious practices as if they were sources of grace. Ultimately, such misdirected devotion signals a deeper loss of awareness of God’s presence, reminding us that even prayer, at its highest expression, moves beyond words into reverent dependence on God alone.

I. WHAT THIS REVEALS.

A. Loss of consciousness of God.

B. People hungering after what has been lost.

C. Confusion.

II. HEZEKIAH'S TWO ACTIONS.

A. Called it "Nehushtan" - a mere thing of brass.

B. He broke it into pieces.

III. APPLICATION TO OUR DAY.

A. God's gifts so abused as to become injurious.

1. Some burning incense to a building.

2. Some to an order of worship.

3. Some to a denomination.

4. Some to old experiences.

5. Prayer ordinances - make them means of grace.

B. What this indicates.

1. Loss of consciousness of God.

2. Savanorola - when prayer reaches its ultimate height, words are impossible.

COMMENT - Savonarola is one of the clearest historical “Nehushtan moments” in church history, and Chuck Smith’s reference fits him perfectly.

Good and historic religious forms had gradually

become substitutes for God Himself.Girolamo Savonarola and the Nehushtan Principle can be understood as a historical embodiment of the same spiritual diagnosis seen in Hezekiah’s destruction of the bronze serpent: good and historic religious forms had gradually become substitutes for God Himself.

Savonarola ministered in late–15th-century Florence amid a church culture saturated with ritualism, relics, indulgences, images, and external religion, while genuine repentance and holiness were largely absent; what he perceived was a loss of consciousness of God, marked by people trusting church forms instead of Christ, relying on rituals as automatic means of grace, treating incense, images, relics, and liturgy as spiritually effective in themselves, and reducing prayer to mechanics rather than communion.

In this sense, Savonarola enacted a “Nehushtan response”: as Hezekiah named the idol for what it truly was—“a mere thing of brass”—and destroyed it, Savonarola exposed religious excess as empty, called people not to reform-by-ritual but to repentance, and led Florence in the Bonfire of the Vanities (1497), where citizens voluntarily burned religious trinkets, images, luxuries, and superstitious objects—not out of hatred for beauty or art, but out of zeal against idolatry.

His teaching that true prayer ultimately transcends words, resting silently in God when it reaches its highest expression, perfectly echoes the principle that ritual prayer is only a means, while silent dependence is the reality—and that anything replacing dependence must be broken.

Relationship over ritual, Spirit over structure,

and reality over religious formThis is why Savonarola so closely aligns with the warnings later emphasized by Chuck Smith, who stressed relationship over ritual, Spirit over structure, and reality over religious form: Savonarola stands as a historical witness to the cost of smashing Nehushtans. Excommunicated, arrested, tortured, and executed in 1498, he did not die for rejecting God, but for threatening an institutional religion that had quietly replaced Him.

Anything which once pointed to God but now replaces living

dependence on God must be named for what it is and brokenThe pattern remains unchanged across history—from Hezekiah’s bronze serpent, to relics and sacred objects, to Savonarola’s images and indulgences, and finally to modern substitutes such as buildings, denominations, liturgies, and past experiences—confirming the enduring truth that anything which once pointed to God but now replaces living dependence on God must be named for what it is and broken; this is "Nehushtan theology," and Savonarola lived—and died—by it.

"NEHUSHTAN"

A. Hezekiah's ascension and action "broke in pieces

B. History of brazen serpent.

1. Israel's complaining.

2. Snake pits.

3. Brazen serpent.

C. Preservation of brazen serpent.

1. Moses wilderness; Joshua conquest; judges David Solomon.

D. Development of worship.

1. Interest grew to veneration.

2. Began to worship symbol.

3. Defied serpent of brass.

E. Story not so old.

The Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan has a

Roman column and, on top of it, a bronze serpent

donated by emperor Basil II in 1007.

1. Church of St. Ambrose - Milan 971 Milanese envoy to Constantinople.

COMMENT - Chuck Smith’s reference to “the Church of St. Ambrose – Milan – 971 – Milanese envoy to Constantinople” is significant because it points to a classic historical example of how a God-given means can become an object of devotion, reinforcing the very lesson of 2 Kings 18:4 (Nehushtan) that he was teaching.

He is alluding to a historical incident from A.D. 971, when a Milanese envoy traveled to Constantinople and recorded his astonishment at Eastern Christian worship practices. He observed believers burning incense and showing reverence to relics, sacred objects, and church furnishings in ways that treated these items as conduits of divine presence rather than as reminders pointing to God. This account later became part of a broader Western critique of Eastern devotional excess, especially the tendency for physical objects to move from symbolic aids into objects of veneration. By referencing this moment, Chuck Smith underscores that this danger is not modern but has surfaced repeatedly throughout church history.

The mention of St. Ambrose and Milan is significant because Ambrose was one of the most respected leaders of the early Western church, and Milan became a major theological and liturgical center known for emphasizing spiritual worship over ritual superstition. By invoking “the Church of St. Ambrose,” Chuck Smith is implicitly appealing to an earlier Western tradition that prized inward devotion before later developments elevated relics, incense, and rituals into quasi-sacramental objects. His point is that even churches with strong spiritual foundations can drift over time into object-centered devotion.

Constantinople, the heart of Byzantine Christianity, is central to the warning because it was there that icons, relics, incense, and sacred objects increasingly took on mediatory roles between worshipers and God. Chuck Smith is not attacking Eastern Christianity as a whole, but highlighting a subtle shift in which reverence slid into reliance—where symbols intended to point to God slowly became substitutes for direct dependence on Him.

The theological point Chuck Smith is making is one he consistently emphasized: the danger of confusing symbols with substance, treating outward forms as sources of grace, and replacing living faith with religious mechanics. The 971 Milan–Constantinople reference serves as a historical illustration of a recurring biblical pattern—God gives a good thing, people cling to it, it begins to replace God, and reform becomes necessary. This is the same pattern seen with the bronze serpent (Nehushtan), temple rituals, relics and icons, and even modern church structures, liturgies, denominations, or spiritual experiences.

Chuck Smith often used church history alongside Scripture to show that while the Bible diagnoses the problem, history proves it recurs, making personal application unavoidable. By citing this event, he was effectively saying, “What happened in Israel happened again in church history—and it can happen to us.” In short, his reference highlights a historical parallel to Nehushtan: a once-meaningful aid to worship became an object of devotion itself. The Milanese envoy’s shock at Constantinople illustrates how sincere worship can drift into idolatry, reinforcing Chuck Smith’s central warning that anything replacing direct dependence on God—no matter how sacred its origin—must be recognized and, if necessary, broken.

I. DEIFICATION - - - SIGN OF PEOPLE AT THE TIME.

A. Sign of their loss of consciousness of God.

B. People hungering after that which they lost.

1. Idol always means this.

2. Sense of need - sense of lack.

C. Sign of confusion, misinterpretation.

1. As though serpent was healing agent of past.

II. HEZEKlAH'S TWOFOLD ACTIONS.

A. Named the serpent "Nehushtan."

1. "A thing of brass."

2. He called it what it was.

3. It was a revelation and shame to the people.

a. they had left worshipping the 14-wing God and began worshipping "a thing of brass."

B. He broke it in pieces.

II. MODERN APPLICATIONS.

A. God's gifts may be so abused as to become injurious.

1. Some of the things people burn incense to:

a. A building, selling the church.

b. Form of worship.

c. Certain evangelists or ministers "I know if he would just pray for me."

d. Past experiences.

e. Creed or denomination.

f. Trust deed (terms of deed...)

2. Sign of loss of fellowship with God.

3. Proper attitude toward these things.

a. Call them what they are:

- church - bricks and mortar

- minister - a man, exercise of

- worship - forms

- creeds - human opinions, trust

- deed - paper

- experiences - past

b. If these things come between you and God, break it in pieces.

B. Paul to Phillipians:

"That which was gain to me I counted loss."

30 years later - "Ye, I count all things but loss."

"I counted yesterday no value unless still counting

today."

C. Light that shone on Damascus Road no value unless still shining today.

SUMMARY: The deification of the bronze serpent was a clear sign of the people’s spiritual condition, revealing a loss of consciousness of God and a hunger to fill the void left by that loss; idols always arise from a sensed lack and a misplaced need. Their confusion led them to misinterpret a former means of God’s grace as a continuing source of power, as though the serpent itself healed rather than the living God. Hezekiah’s response was decisive and instructive: first, he named the serpent Nehushtan—“a mere thing of brass”—stripping it of false glory and exposing the shameful reality that they had exchanged worship of the living God for a mere object; second, he broke it in pieces, removing the obstacle to true worship. The lesson carries enduring relevance, for God’s gifts can be so abused that they become injurious—buildings, forms of worship, ministers, past experiences, creeds, or institutions may all become substitutes for God Himself. The proper response is to call these things what they truly are and, if they stand between the soul and God, to break them decisively. As Paul testified, what once seemed gain must continually be counted loss, for yesterday’s light has no value unless it is still shining today.

Nehushtan —

When God’s Gifts Replace God

The history of the bronze serpent (Numbers 21:6–9) reveals a gracious paradox: Israel’s rebellion brought divine judgment, yet God provided deliverance through a simple act of faith—looking at a bronze serpent lifted on a pole. The bronze itself held no power; healing came because looking was an act of obedient trust in God’s word. Jesus later identified this event as a type pointing to Himself (John 3:14–16), teaching that just as the serpent was lifted up under judgment, so He would be lifted up on the cross to bear sin, so that all who look to Him in faith might live. Tragically, what began as a God-appointed means of grace became, centuries later, an object of worship. The bronze serpent was preserved for nearly 700 years until, in the days of Hezekiah, Israel burned incense to it as though it possessed divine power. Hezekiah responded decisively: he stripped it of false sanctity by naming it Nehushtan—“a mere piece of bronze”—and then broke it in pieces (2 Kings 18:4), exposing the shameful exchange of the living God for an object.

This act reveals a timeless spiritual diagnosis. When people lose a living awareness of God’s presence, they grow hungry to recapture what has been lost—former joy, power, or intimacy with God—and they often cling to relics, places, traditions, rituals, or past experiences as substitutes. Idolatry always arises from a sensed lack and confusion between means and object: what once pointed to God is mistaken for God Himself. As Chuck Smith repeatedly emphasized, God’s gifts can be so abused that they become injurious—buildings, forms of worship, denominations, ministers, liturgies, prayer practices, or memories of past encounters may quietly replace present dependence on God. When this happens, they must be called what they are and, if necessary, broken.

Church history confirms the same pattern. Girolamo Savonarola embodied a historical “Nehushtan moment” in late–15th-century Florence, where relics, images, indulgences, and ritual had become substitutes for repentance and living faith. His call to smash religious excess—dramatically expressed in the Bonfire of the Vanities—was not an attack on beauty or history, but a protest against objects and forms that had replaced dependence on God. Likewise, the A.D. 971 account of a Milanese envoy observing relic-centered devotion in Constantinople illustrates how even sincere worship can drift into reliance on symbols rather than God Himself. In every age, the danger is the same: confusing symbols with substance, ritual with reality, and history with living faith.

The enduring lesson of Nehushtan is therefore clear and searching: past encounters with God have no saving or sustaining value unless they are carried forward into present obedience, faith, and dependence. Buildings are bricks and mortar, rituals are forms, ministers are men, creeds are human formulations, and experiences belong to yesterday. As Paul testified (Philippians 3:13–14), yesterday’s gain must continually be counted loss unless it is still shaping today’s walk with God. Anything that once pointed to God but now replaces living reliance on Him must be named for what it is—Nehushtan, nothing more than brass—and removed, so that worship may return to its proper object: the living God alone. (AI SUMMARY)

Relationship over ritual.

Spirit over structure.

Reality over religious form.