THE CONVERSION OF

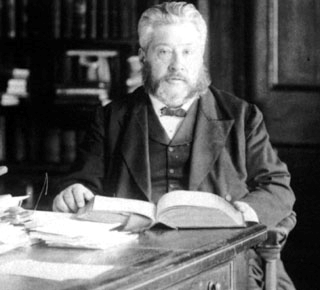

CHARLES SPURGEON

(His Personal Testimony)

Look unto Me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth:

for I am God, and there is none else.

Isaiah 45:22KJV

This is the text that changed a man's eternal destiny from hell to heaven, from eternal destruction to eternal glory in Christ. Read Spurgeon's own words of how God's providence and God's grace intersected to save his soul forever...

In my conversion, the very point lay in making the discovery that I had nothing to do but To look to Christ and I should be saved. I believe that I had been a very good, attentive hearer; my own impression about myself was that nobody ever listened much better than I did. For years, as a child, I tried to learn the way of salvation; and either I did not hear it set forth, which I think cannot quite have been the case, or else I was spiritually blind and deaf, and could not see it and could not hear it; but the good news that I was, as a sinner, to look away from myself to Christ, as much startled me, and came as fresh to me, as any news I ever heard in my life. Had I never read my Bible? Yes, and I read it earnestly. Had I never been taught by Christian people? Yes, I had, by mother, and father, and others. Had I not heard the gospel? Yes, I think I had; and yet, somehow, it was like a new revelation to me that I was to ''believe and live.'' I confess to have been tutored in piety, put into my cradle by prayerful hands, and lulled to sleep by songs concerning Jesus; but after having heard the gospel continually, with line upon line, precept upon precept, here much and there much, yet, when the Word of the Lord came to me with power, it was as new as if I had lived among the unvisited tribes of Central Africa, and had never heard the tidings of the cleansing fountain filed with blood, drawn from the Savior's veins.

When, for the first time, I received the gospel to my soul's salvation, I thought that I had never really heard it before, and I began to think that the preachers to whom I had listened had not truly preached it. But, on looking back, I am inclined to believe that I had heard the gospel fully preached many hundreds of times before, and that this was the difference,--that I then heard it as though I heard it not; and when I did hear it, the message may not have been any more clear in itself than it had been at former times, but the power of the Holy Spirit was present to open my ear, and to guide the message to my heart….

I sometimes think I might have been in darkness and despair until now had it not been for the goodness of God in sending a snowstorm, one Sunday morning, while I was going to a certain place of worship. When I could go no further, I turned down a side street, and came to a little Primitive Methodist Chapel. In that chapel there may have been a dozen or fifteen people. I had heard of the Primitive Methodists, how they sang so loudly that they made people's heads ache; but that did not matter to me. I wanted to know how I might be saved, and if they could tell me that, I did not care how much they made my head ache. The minister did not come that morning; he was snowed up, I suppose. At last, a very thin-looking man, a shoemaker, or tailor, or something of that sort, went up into the pulpit to preach. Now, it is well that preachers should be instructed; but this man was really stupid. He was obliged to stick to his text, for the simple reason that he had little else to say. The text was,--'

LOOK UNTO ME, AND BE YE SAVED,

ALL THE ENDS OF THE EARTH.

Isaiah 45:22KJV

He did not even pronounce the words rightly, but that did not matter. There was, I thought, a glimpse of hope for me in that text. The preacher began thus:--'

'My dear friends, this is a very simple text indeed. It says, 'Look.' Now lookin' don't take a deal of pains. It ain't liftin' your foot or your finger; it is just, 'Look.' Well, a man needn't go to College to learn to look. You may be the biggest fool, and yet you can look. A man needn't be worth a thousand a year to be able to look. Anyone can look; even a child can look. But then the text says, 'Look unto Me.' Ay!'' said he, in broad Essex, ''Many on ye are lookin' to yourselves, but it's no use lookin' there. You'll never find any comfort in yourselves. Some look to God the Father. No, look to Him by-and-by. Jesus Christ says, 'Look unto Me.' Some on ye say, 'We must wait for the Spirit's workin'.' You have no business with that just now. Look to Christ. The text says, 'Look unto Me.' ''

Then the good man followed up his text in this way:--

''Look unto Me; I am sweatin' great drops of blood. Look unto Me; I am hangin' on the cross. Look unto Me; I am dead and buried. Look unto Me; I rise again. Look unto Me; I ascend to Heaven. Look unto Me; I am sittin' at the Father's right hand. O poor sinner, look unto Me! Look unto Me!''

When he had gone to about that length, and managed to spin out ten minutes or so, he was at the end of his tether. Then he looked at me under the gallery, and I daresay, with so few present, he knew me to be a stranger. Just fixing his eyes on me, as if he knew all my heart, he said,

''Young man, you look very miserable.''

Well, I did; but I had not been accustomed to have remarks made from the pulpit on my personal appearance before. However, it was a good blow, struck right home. He continued,

''and you always will be miserable--miserable in life, and miserable in death,--if you don't obey my text; but if you obey now, this moment, you will be saved.''

Then, lifting up his hands, he shouted, as only a Primitive Methodist could do,

''You man, look to Jesus Christ. Look! Look! Look! You have nothin' to do but to look and live.''

I saw at once the way of salvation. I know not what else he said,--I did not take much notice of it -- I was so possessed with that one thought. Like as when the brazen serpent was lifted up, the people only looked and were healed, so it was with me. I had been waiting to do fifty things, but when I heard that word, ''Look!'' what a charming word it seemed to me! Oh! I looked until I could almost have looked my eyes away. There and then the cloud was gone, the darkness had rolled away, and that moment I saw the sun; and I could have risen that instant, and sung with the most enthusiastic of them, of the precious blood of Christ, and simple faith which looks alone to Him. Oh, that somebody had told me this before, ''Trust Christ, and you shall be saved.''…

It is not everyone who can remember the very day and hour of his deliverance; but, as Richard Knill said, ''At such a time of the day, clang went every harp in Heaven, for Richard Knil was born again,'' it was e'en so with me. The clock of mercy struck in Heaven the hour and moment of my emancipation, for the time had come. Between half-past ten o'clock, when I entered that chapel, and half-past twelve o'clock, when I was back again at home, what a change had taken place in me! I had passed from darkness into marvelous light, from death to life.

Simply by looking to Jesus, I had been delivered from despair, and I was brought into such a joyous state of mind that, when they saw me at home, they said to me, ''Something wonderful has happened to you;'' and I was eager to tell them all about it….I have always considered, with Luther and Calvin, that the sum and substance of the gospel lies in that word Substitution, --Christ standing in the stead of man. If I understand the gospel, it is this: I deserve to be lost for ever; the only reason why I should not be damned is, that Christ was punished in my stead, and there is no need to execute a sentence twice for sin. On the other hand, I know I cannot enter Heaven unless I have a perfect righteousness; I am absolutely certain I shall never have one of my own, for I find I sin every day; but then Christ had a perfect righteousness, and He said, ''There, poor sinner, take My garment, and put it on; you shall stand before God as if you were Christ, and I will stand before God as if I had been the sinner; I will suffer in the sinner's stead, and you shall be rewarded for works which you did not do, but which I did for you.'' I find it very convenient every day to come to Christ as a sinner, as I came as the first. ''You are no saint,'' says the devil. Well, if I am not, I am a sinner, and Jesus Christ came into the world to save sinners. Sink or swim, I go to Him; other hope I have none. By looking to Him, I received all the faith which inspired me with confidence in His grace; and the word that first drew my soul--''Look unto Me,''--still rings its clarion note in my ears. There I once found conversion, and there I shall ever find refreshing and renewal.

The story he told over 280 times in his sermons

I was years and years upon the brink of hell—I mean in my own feeling. I was unhappy, I was desponding, I was despairing. I dreamed of hell. My life was full of sorrow and wretchedness, believing that I was lost.”

Charles Spurgeon used these strong words to describe his adolescent years. Despite his Christian upbringing (he was christened as an infant, and raised in the Congregational church), and his own efforts (he read the Bible and prayed daily), Spurgeon woke one January Sunday in 1850 with a deep sense of his need for deliverance.

Because of a snowstorm, the 15-year-old’s path to church was diverted down a side street. For shelter, he ducked into the Primitive Methodist Chapel on Artillery Street. An unknown substitute lay preacher stepped into the pulpit and read his text—Isaiah 45:22—“Look unto me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth; for I am God, and there is none else.”

Spurgeon’s Autobiography records his reaction:

“He had not much to say, thank God, for that compelled him to keep on repeating his text, and there was nothing needed—by me, at any rate except his text. Then, stopping, he pointed to where I was sitting under the gallery, and he said, ‘That young man there looks very miserable’ … and he shouted, as I think only a Primitive Methodist can, ‘Look! Look, young man! Look now!’ … Then I had this vision—not a vision to my eyes, but to my heart. I saw what a Savior Christ was.… Now I can never tell you how it was, but I no sooner saw whom I was to believe than I also understood what it was to believe, and I did believe in one moment.

“And as the snow fell on my road home from the little house of prayer I thought every snowflake talked with me and told of the pardon I had found, for I was white as the driven snow through the grace of God.”

Upon his return home, his appearance caused his mother to exclaim, “Something wonderful has happened to you.”

For the next months young Spurgeon searched the Scriptures “to know more fully the value of the jewel which God had given me.… I found that believers ought to be baptized.” And so he was baptized, by immersion, four months later in the River Lark, after which he joined a Baptist church.

RECOMMENDATION: If you enjoy reading stories of the redeeming work of God's grace than bookmark this short (71 page) book by Hy Pickering entitled "TWICE BORN MEN." Therein you find the testimonies of some men you have heard of and some you have not, but your soul will be blessed as you are reminded of our great God Who is always "Mighty to Save." (Isaiah 63:1+). See also Frank Boreham's A Book of Everlastings

A collection of true and unusual facts about Charles Haddon Spurgeon

Charles Haddon Spurgeon is history’s most widely read preacher (apart from the biblical ones). Today, there is available more material written by Spurgeon than by any other Christian author, living or dead.

One woman was converted through reading a single page of one of Spurgeon’s sermons wrapped around some butter she had bought.

Spurgeon read The Pilgrim’s Progress at age 6 and went on to read it over 100 times.

The New Park Street Pulpit and The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit—the collected sermons of Spurgeon during his ministry with that congregation fill 63 volumes. The sermons’ 20–25 million words are equivalent to the 27 volumes of the ninth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. The series stands as the largest set of books by a single author in the history of Christianity.

A caricature of Spurgeon (shown preaching in the Metropolitan Tabernacle’s “crow’s nest”) from the December 10, 1870, edition of Vanity Fair. The drawing was number 16 in the magazine’s “Men of the Day” series. The accompanying text described Spurgeon as “honest, resolute, and sincere; lively, entertaining, and when he pleases, jocose.”

Spurgeon’s mother had 17 children, nine of whom died in infancy.

When Charles Spurgeon was only 10 years old, a visiting missionary, Richard Knill, said that the young Spurgeon would one day preach the gospel to thousands and would preach in Rowland Hill’s chapel, the largest Dissenting church in London. His words were fulfilled.

Spurgeon missed being admitted to college because a servant girl inadvertently showed him into a different room than that of the principal who was waiting to interview him. (Later, he determined not to reapply for admission when he believed God spoke to him, “Seekest thou great things for thyself? Seek them not!”)

Spurgeon’s personal library contained 12,000 volumes—1,000 printed before 1700. (The library, 5,103 volumes at the time of its auction, is now housed at William Jewell College in Liberty, Missouri.)

Before he was 20, Spurgeon had preached over 600 times.

Spurgeon drew to his services Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone, members of the royal family, Members of Parliament as well as author John Ruskin, Florence Nightingale, and General James Garfield, later president of the United States.

The New Park Street Church invited Spurgeon to come for a 6-month trial period, but Spurgeon asked to come for only 3 months because “the congregation might not want me, and I do not wish to be a hindrance.”

When Spurgeon arrived at The New Park Street Church in 1854, the congregation had 232 members. By the end of his pastorale, 38 years later, that number had increased to 5,311. (Altogether, 14,460 people were added to the church during Spurgeon’s tenure.) The church was the largest independent congregation in the world.

Spurgeon typically read 6 books per week and could remember what he had read—and where—even years later.

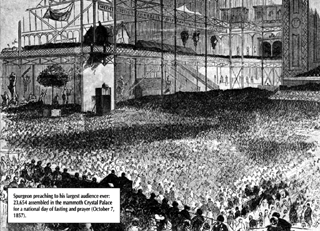

Spurgeon once addressed an audience of 23,654 without a microphone or any mechanical amplification.

Spurgeon began a pastors’ college that trained nearly 900 students during his lifetime—and it continues today.

In 1865, Spurgeon’s sermons sold 25,000 copies every week. They were translated into more than 20 languages.

At least 3 of Spurgeon’s works (including the multi-volume Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit series) have sold more than 1,000,000 copies. One of these, All of Grace, was the first book ever published by Moody Press (formerly the Bible Institute Colportage Association) and is still its all-time bestseller.

During his lifetime, Spurgeon is estimated to have preached to 10,000,000 people.

Spurgeon once said he counted 8 sets of thoughts that passed through his mind at the same time while he was preaching.

Testing the acoustics in the vast Agricultural Hall, Spurgeon shouted, “Behold the Lamb of God which taketh away the sin of the world.” A worker high in the rafters of the building heard this and became converted to Christ as a result.

Spurgeon preaching in Exeter Hall in London.

Susannah Thompson, Spurgeon’s wife, became an invalid at age 33 and could seldom attend her husband’s services after that.

Spurgeon spent 20 years studying the Book of Psalms and writing his commentary on them, The Treasury of David.

Spurgeon insisted that his congregation’s new building, the Metropolitan Tabernacle, employ Greek architecture because the New Testament was written in Greek. This one decision has greatly influenced subsequent church architecture throughout the world.

The theme for Spurgeon’s Sunday morning sermon was usually not chosen until Saturday night.

For an average sermon, Spurgeon took no more than one page of notes into the pulpit, yet he spoke at a rate of 140 words per minute for 40 minutes.

The only time that Spurgeon wore clerical garb was when he visited Geneva and preached in Calvin’s pulpit.

By accepting some of his many invitations to speak, Spurgeon often preached 10 times in a week.

Spurgeon met often with Hudson Taylor, the well-known missionary to China, and with George Müller, the orphanage founder.

Spurgeon had two children—twin sons—and both became preachers. Thomas succeeded his father as pastor of the Tabernacle, and Charles, Jr., took charge of the orphanage his father had founded.

A London street scene, circa 1885, near Spurgeon’s church, the Metropolitan Tabernacle. Conductors of horse-drawn buses in north London used to attract people by calling, “Over the water [Thames River] to [hear] Charlie.”

Spurgeon’s wife, Susannah, called him Tirshatha (a title used of the Judean governor under the Persian empire), meaning “Your Excellency.”

Spurgeon often worked 18 hours a day. Famous explorer and missionary David Livingstone once asked him, “How do you manage to do two men’s work in a single day?” Spurgeon replied, “You have forgotten that there are two of us.”

Spurgeon spoke out so strongly against slavery that American publishers of his sermons began deleting his remarks on the subject.

Occasionally Spurgeon asked members of his congregation not to attend the next Sunday’s service, so that newcomers might find a seat. During one 1879 service, the regular congregation left so that newcomers waiting outside might get in; the building immediately filled again.

He was the quintessential Victorian Englishman, yet his masterful preaching astonished his era—and lives long beyond it.

Next year marks the centennial of the death of the English Baptist preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon. When Spurgeon died, in January 1892, London south of the Thames went into mourning. Sixty thousand people came to pay homage during the three days his body lay in state at the Metropolitan Tabernacle. A funeral parade two miles long followed his hearse from the Tabernacle to the cemetery at Upper Norwood. One hundred thousand people stood along the way, flags flew at half-mast, shops and pubs were closed. It was a remarkable demonstration of affection and respect, even in an era when people were scrupulous in observing the rituals that accompanied death.

Spurgeon died in the same month as Cardinal Manning and Prince Edward. Newspapers and periodicals observed the coincidence with special issues, bordered in black, featuring the portraits of the three men. Manning, a famous convert and a prince of the Roman Catholic Church; Edward, Duke of Clarence, the dull grandson of Queen Victoria; and Spurgeon, the fiercely anti-Catholic evangelical preacher—they constituted a curious mix, even in the pages of the lachrymose penny press. The Duke lacked character or intelligence but was born to great things. Manning, a man of exceptional abilities and powerful connections, had been marked from an early age as one destined to achieve power in church or politics. Charles Spurgeon had none of these advantages of privilege, education, or aristocratic connections. He traveled a more difficult road to his position of eminence, and his is the most remarkable story of the three.

Weaned on Foxe’s Book of Martyrs

Spurgeon was born in 1834, in Kelvedon, Essex, an area with a long tradition of Protestant resistance dating back to the persecutions of “Bloody Mary” in the sixteenth century. His father, John, and his grandfather, James, were Independent ministers. Like many nineteenth-century Nonconformist ministers, Spurgeon was a “son of the manse.” His earliest childhood memories were of listening to sermons, learning hymns, and looking at the pictures in The Pilgrim’s Progress and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. He would later recommend Foxe’s book as “the perfect Christmas gift for a child,” and it was clearly one of the most significant works he ever read, vividly shaping his attitudes toward established religions, the tyranny of Rome, and the glory of martyrdom. The brave Protestants who were burned at Smithfield, and the valiant Puritans, such as Bunyan, who were jailed for their beliefs, were his childhood heroes. And they remained his heroes and models in the years when he evoked their example to the thousands who came to hear him in the Tabernacle and the tens of thousands who read his sermons each week.

The house in Kelvedon, Essex, in which Charles Spurgeon was born on July 19, 1834. His father, John, an Independent minister and part-time accountant, moved the family 10 months later, probably because of financial difficulties.

Rural Values

For much of his childhood, Spurgeon lived with his grandparents and Aunt Anne in the small agricultural village of Stambourne. There were about five hundred people in Stambourne, a town so remote that even at the end of the nineteenth century it lacked a railroad station. The revolutions in industry and transportation that transformed Victorian Britain were unknown to Stambourne, where the pace of life revolved around the seasons rather than the machine. Spurgeon’s grandfather preached in an Independent meeting house that dated back to the seventeenth century.

Ten years after leaving Stambourne, Spurgeon began his London ministry, and for the rest of his life the metropolis was his home. Yet he was never truly comfortable in an urban setting. All his life he continued to return to Stambourne, hoping to find in that tranquil setting some respite from the hectic pace of city life. His roots and values remained those of rural, pre-industrial Britain.

Spurgeon expressed these roots and values most notably, perhaps, in his popular John Ploughman’s Talk, Being Plain Talk for Plain People. The fictional character of John Ploughman was modeled upon Will Richardson, a farmer and neighbor in Stambourne; but there was much of Spurgeon as well in the blunt, opinionated, and humorous ploughman. John, like his creator, was a man of the people, with “no trimming in him.” His common-sense wisdom and vernacular wit struck a chord among readers uneasy with the rapid shift from a rural society to an urban one.

During Spurgeon’s lifetime, for the first time, a majority of Britons came to live in cities. For many, the result was alienation, displacement, a lack of tradition, and an end of purposeful work. Spurgeon shared the misgivings about the disappearance of the old England, but he never lost his faith in the fundamental decency of ordinary Englishmen. He understood the values of faith, kinship, and meaningful work that had given purpose to the lives of villagers for centuries. And he was able to recall those values to urban congregations in such a plain and compelling manner that he seemed to many to embody all that was quintessentially English. In Dr. John Watson’s words, Spurgeon was “as characteristic an Englishman as our generation has produced.”

The manse and Independent meeting house in the rural village of Stambourne. Spurgeon came here when he was only about 14 months old, to be cared for by his grandparents and aunt, and he stayed until he was age 6. He often visited Stambourne later, saying that “there is no other village in all the world half so good as that particular village!”

Education and Conversion

Spurgeon’s formal education, by nineteenth-century standards, was mediocre. After returning to live with his parents in Colchester, he attended a local school for a few years, and then for a brief time was an usher (or teaching assisant) at an Anglican school in Newmarket where a maternal uncle was a master. He moved to Cambridge in 1850, and he lived in the Cambridge area until he began his London ministry four years later. During his years in Cambridge he combined the roles of scholar, teaching assistant, and preacher. He was briefly tutored in Greek, but his acquaintance with the classics was fleeting in a period in which the undergraduate curriculum was overwhelmingly classical, and knowledge of classical languages was assumed to be the prerequisite to scholarship. As a Dissenter, Spurgeon could not at that time take a degree at Oxford or Cambridge, but there were excellent Dissenting academies and denominational colleges open to him. But Spurgeon decided that he would not seek formal ministerial training. His example was unusual, even among the Baptists.

Although Spurgeon did not attend a college, he valued learning and loved books. He collected Puritan editions, and his personal library of twelve thousand volumes contained one thousand works published before 1700. He was a literate man with a remarkable command of language that the exacting critic John Ruskin was not alone in finding “very wonderful!”

Spurgeon broke with his family’s Independent religious tradition when he decided, at age 15, to become a Baptist. His mother’s reaction, “I often prayed the Lord to make you a Christian, but I never asked that you might become a Baptist,” suggests the dismay that his family must have felt at his decision. There is a hint of youthful rebellion in his move. Spurgeon had become convinced while he was still a schoolboy that the ritual of infant baptism, practiced by his father and grandfather, was unscriptural. When he endured the adolescent agonies of religious doubt, he admitted that his father was “the last person I should have elected to speak to upon religion.”

Spurgeon attributed his conversion to a sermon he heard by chance when a snowstorm blew him away from his destination and into a Primitive Methodist chapel. The event reinforced his conviction that truth was more likely to be found among the poor and humble than among the overeducated and refined. When he established his own pastors’ college, there were no academic requirements for admission.

The Preaching “Boy Wonder”

Spurgeon began preaching in rural Cambridgeshire when he was barely in his teens. His first pastorale was in the village of Waterbeach, a few miles from the university. Spurgeon was not average; even as a teenaged pastor in a country town he had star quality. Before he was “the preaching sensation of London,” he was “the boy wonder of the fens.” He was small in stature, and in his youth pale and slim, appearing even younger than he was. His boyish appearance was in startling contrast to the maturity of his sermons, which naturally were strongly influenced by the Puritan works he had studied since childhood. He had a retentive memory and always spoke extemporaneously from an outline. His youth, energy, and oratorical skills, combined with his command of old-fashioned texts, made a vivid impact upon his congregations. People trekked from miles away to hear the preaching prodigy of Waterbeach. Within eighteen months his reputation had spread to London, and he was invited to preach at the historic New Park Street Chapel. The congregation at New Park Street was impressed by the visitor and voted—with only five “nays”—to invite him preach for an additional six months. The 19-year-old country-bred boy preacher moved to the city.

In the early years of Spurgeon’s career, he preached in London and throughout the kingdom. No chapel seemed large enough to hold the people who wanted to hear him, and he moved into London’s great secular halls—Exeter Hall, Surrey Gardens Music Hall, the Agricultural Hall—where he preached to thousands. In 1861, his congregation moved to the new Metropolitan Tabernacle, and Spurgeon left London less frequently.

Spurgeon’s Popularity

The period of Spurgeon’s early London ministry was a period of considerable economic and social distress in Britain. Cholera was a great scourge: Twenty thousand died in 1854, Spurgeon’s first year in London. Also in that year, the Crimean War broke out, the first war involving the major European powers since Waterloo. The mutiny of the Seypoys in India in 1857 provoked a tremendous outpouring of rage and grief, concluding in a National Day of Fast and Humiliation during which Spurgeon addressed the largest audience of his life: twenty-four thousand gathered in the Crystal Palace. These events, with the economic disruptions caused by the outbreak of the American Civil War, brought suffering and economic ruin to many, who sought religious solace in confused and troubled times. Not coincidentally, the 1850s ended with the “Great Revival,” which began in Ireland and Scotland and swept into England, igniting religious emotions in a fashion not seen in Britain since the days of Wesley and Whitefield. Spurgeon disdained the title of “revivalist,” but his ministry clearly benefited from the religious enthusiasm sparked by the events of 1859.

Some of Spurgeon’s popularity in the mid-Victorian years can also be attributed to the fact that going to church was one of the few Sabbath diversions permitted in an evangelical household. It is difficult to exaggerate the change for many evangelical families when the Sabbath dawned. Books and papers were put away, games were forbidden, and any secular amusement was out of the question. John Ruskin’s mother, for example, turned all of the pictures in the house face-to-the-wall. For many Victorians, attending a Sunday service—indeed, attending several Sunday services—was a satisfying way to fill the void. Although an evangelical would never attend a theater, he or she could have a theatrical experience by going to hear the young Spurgeon preaching before thousands in Exeter Hall.

And Spurgeon was a compelling, charismatic speaker—as his friend John Carlile remembered, “dramatic to his fingertips.” Photographs from this period show him assuming dramatic stances, and visitors’ accounts tell us he seemed to act out the parts, to assume the identity of the biblical characters he spoke of. Before age and gout slowed him down, Spurgeon paced the platform and even ran from side to side. His sermons were filled with sentimental stories that ordinary people could relate to: tales of dying children, grieving parents, repentant harlots, and servants wiser than their masters.

Spurgeon’s language was graphic, emotionally charged, occasionally maudlin and sentimental. But great actors, novelists, and preachers of the era appealed to emotions. People cried when Little Nell died and when Little Eva went to heaven. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the best-selling novel in nineteenth-century Britain. The evangelical appeal to emotions led to the abolition of the slave trade and brought the condition of the child factory worker to the attention of the public. Because of emotional appeals, lives were changed and desperate people were given hope.

Spurgeon’s Critics

The dramatic devices employed by Spurgeon have become commonplace now. But they were novel in the mid-Victorian years, and many critics roundly condemned the young minister’s style, manner, and appearance. He was called “a clerical poltroon,” “the Exeter Hall demagogue,” and “the pulpit buffoon.” His ministry was dismissed as a nine days’ wonder, and he was compared to popular entertainers such as Tom Thumb, the clown at Astley’s Circus, the Living Skeleton, and a whole range of fire eaters, flying men, and tightrope walkers who briefly captured the attention of the fickle populace. Other ministers were openly contemptuous of his “sensationalism,” although many would eventually copy his style and even appropriate his sermons.

Spurgeon survived the hostile reviews and learned to live with the jealousies of his fellow ministers. He proved to his critics that he had staying power, and he earned the respect of those who had been quick to denounce “Spurgeonism” as a passing fad on a spiritual level with table rapping. In preaching, as in most things, nothing succeeds like success, and when Spurgeon moved his flock into the new Tabernacle in Southwark in 1861, it was fully paid for. The new building could seat six thousand people, and when Spurgeon stood on his platform—he hated conventional pulpits—he looked out at the largest Protestant congregation in the world. In the words of the title of his first biography, he had gone From the Usher’s Desk to the Tabernacle.

Spurgeon was sometimes called “the Pope at Newington Butts.” He certainly ruled his congregation with a firm hand, although perhaps the best analogy would be to an enlightened despot rather than to the pope. Every person who joined his huge congregation was personally interviewed by Spurgeon, who wanted to be sure the candidate’s conversion was genuine. His deacons adored him to the point of idolatry. One, presumably speaking for all, declared that if the pastor ever encountered a ditch, they would fill the ditch with their bodies so that he could cross over. “That,” said Spurgeon, “was grand talk.”

Spurgeon’s congregation was not fashionable; most members were lower middle class, although comfortable enough and eminently respectable. In later days his congregation provided him with private rail cars and expense-paid vacations to Mentone, France, a favorite resort of affluent Victorians. His Tabernacle base was comfortable and secure, and he knew it. As one impressed reporter put it, “He spoke of his thousands as lightly as the Shah of Persia.”

This keepsake shows Spurgeon and his young love, Susannah Thompson. Susie was a parishoner at New Park Street Church, and she was baptized by Spurgeon, then her fiancé, in 1855. The following year the two married and had their only children—twin sons Charles, Jr., and Thomas.

Spurgeon’s Love

From all accounts, Spurgeon’s congregation was evenly divided between males and females, which was unusual in a century in which many congregations in Britain and the United States became increasingly female. Spurgeon exuded an air of comfortable masculinity, and women clearly found him attractive. Before his marriage he was deluged with hand-sewn slippers and requests for locks of hair.

In 1856, Spurgeon married Susannah Thompson, a member of his congregation and the daughter of a prosperous ribbon manufacturer. She was trim, pretty, and stylishly dressed in the crinolines and bonnets popular in the mid-Victorian years. By her account, it was not love at first sight. She thought the young preacher countrified. But he was a persistent suitor. The Crystal Palace, site of the Great Exhibition of 1851, had been recently dismantled and moved from Hyde Park to the London suburb of Sydenham. Susannah and Charles each bought season tickets. Here, in Paxton’s vast exhibit halls of iron and glass, the two wandered amid the stuffed elephants, monstrously ornate furniture, faux ruins, sewing machines, threshers, and other mechanical marvels and oddities that entranced visitors. It was a suitable Victorian backdrop for a courtship that had all the charm of an old-fashioned valentine.

They were married, went to Paris for a honeymoon, and within the year were the parents of twin sons, Charles and Thomas. The marriage was a source of strength and abiding comfort to both. Both suffered periodic illness and invalidism. The trim figures of youth became more ample in middle age, but they remained devoted lovers, each seeking the word or token that would lighten the burden of the other. The Spurgeons lived at a time when gender roles were clearly defined, and neither was of the temperament to challenge the prevailing view that man’s sphere was the world and woman was “the angel in the house.”

Spurgeon’s Controversies

Spurgeon was a public figure, and as a public figure with strong convictions, he was often the center of controversy. This was inevitable, but unfortunate, for those who knew him well believed that he was not at his best in controversial situations. He was an eloquent and persuasive speaker, but he was not a good debater, and he paid a heavy emotional and physical price for his involvement in theological and political controversies. But upon certain subjects—Rome, ritualism, hypocrisy, or modernism—he was incapable of moderation. The tragedy was that in all the controversies in which he was involved, there were good and honorable men on both sides.

“The Grand Old Man” of British politics, W. E. Gladstone, four times prime minister of Britain, was Spurgeon’s political hero. Gladstone entered the House of Commons in the year that Spurgeon was born, and in writing to him, Spurgeon referred to him as his “Chief.” The two were much alike: both deeply religious, both emotional and easily moved to tears, both passionately committed to principle. From the 1860s to the 1880s, Spurgeon was an ardent political Dissenter, active on behalf of the Liberal Party and Gladstone. If he did not quite tell his congregation to vote for Gladstone’s party, he came very close. And he did denounce Disraeli (Gladstone’s opponent) in sermons and passed out handbills in support of Liberal candidates. Gladstone attended a service at the Tabernacle, and he invited Spurgeon to dine at Number Ten Downing Street. But when that great man of principle, Mr. Gladstone, became convinced that justice for Ireland meant Home Rule, he split his party and lost Spurgeon’s support. For Spurgeon, Home Rule meant Rome Rule, and in his memory the faggots of Smithfield would begin to glow, and the cries of the martyrs would call him to resistance.

Gladstone split his party, and Spurgeon split his denomination. In the 1880s, about the time Spurgeon broke with the Liberals, he began to express fears that some ministers in his own conservative Baptist sect had become tainted with modernism. He worried that these preachers no longer subscribed to evangelical teaching such as scriptural infallibility, the atonement, and eternal damnation.

The “Down-Grade Controversy,” as it came to be known, pitted Baptist against Baptist, minister against minister, and even some Spurgeon’s College men against Spurgeon. The controversy darkened Spurgeon’s last years, already made bleak by physical debility, and led to charges by supporters that he had been killed by the controversy and died “a martyr to faith.” Spurgeon withdrew from the Baptist Union. The Union, in retaliation, passed what came to be termed “a vote of censure” on the most famous Baptist in the world. Spurgeon ended his life where he began it, in independency, a man too big to be defined by a single denomination or party.

The Preacher’s Preacher

“When our lives come to be written at last,” Spurgeon once wrote, “God grant that they be not only our sayings, but our sayings and doings.” A fair assessment of Spurgeon’s life must include both.

He was not an original thinker, and he never claimed to be a theologian. He was a preacher, and in that role he was unsurpassed in his day and not often matched since. His originality as a preacher lay in his combination of old-fashioned doctrine and up-to-date delivery. He may have been an ordinary and conventional Victorian in many of his personal tastes and prejudices, but he had an uncanny ability to sense the pulse of his times, and to know, almost instinctively, how to reach out to ordinary and troubled people in a language which they could not resist. It was the language of the marketplace—pithy, pungent, often humorous, and at once commonsensical and compelling. The power of that language reached a worldwide audience and has kept the name and message of Spurgeon alive long after the embers of old controversies have died out.

“I must and I will make the people listen,” the boy preacher said. None did it better.

THE POWER OF

GOD'S WORD

Charles Haddon Spurgeon experienced the power (dunamis) of God's Word which is "able (dunamai in present tense = God's Word continually has this inherent or intrinsic ability - no other writing can make such a claim) to give you the wisdom that leads to salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus" (2 Timothy 3:15+). It therefore behooves us to focus our attention on the Word, not men's writings about the Word (including even those you are now reading!)

James echoes the dunamis power of God's Word…

Therefore putting aside all filthiness and all that remains of wickedness, in humility receive the word implanted, which is able (dunamai in present tense = continually able) to save your souls. (James 1:21+)

The Scripture describes the Gospel which "is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes" (Romans 1:16+) and they do point the sinner to the Savior Christ Jesus, the One Who saves unregenerate men and women who exercise sincere faith (2 Timothy 1:5+) in Him.

Paul describes the energizing effect of the Word of God in his first epistle to the Thessalonians…

And for this reason we also constantly thank God that when you received (paralambano) from us the Word of God's message, you accepted (dechomai) it not as the word of men, but for what it really is, the Word of God, which also performs (energeo - energizes, works effectively - present tense = the Word of God continually performs) its work in you who believe. (1 Thessalonians 2:13+)

Related Resources:

Spurgeon experienced the power of God's Word and went on to become one of the greatest preachers of God's powerful Word. The following Spurgeon anecdote beautifully illustrates the supernatural power of God's Word…

The renowned preacher C H Spurgeon once tested an auditorium in which he was to speak that evening. Stepping into the pulpit, he loudly proclaimed, "Behold the lamb of God Who takes away the sin of the world." (John 1:29) Satisfied with the acoustics, he left and went his way. Unknown to him, there were two men working in the rafters of that large auditorium, neither one a Christian. One of the men was pricked in his conscience by the verse Spurgeon quoted and became a believer later that day! Such is the penetrating power of God's eternal word!Little wonder that Paul is so insistent on our "preaching of the Word" (2 Timothy 4:2+)

by LEWIS A. DRUMMOND

The noted German pastor and theologian Helmut Thielicke once said, “Sell all [the books] that you have … and buy Spurgeon.”

Today—nearly a century after Spurgeon’s death—there is more material in print by Charles Haddon Spurgeon than by any other Christian author, living or dead.

What was it about the Victorian London orator that enabled him to captivate the minds and hearts of multitudes—then and now?

Spurgeon preaching to his largest audience ever:

23,654 assembled in the mammoth Crystal palace

for a national day of fasting and prayer (October 7, 1857).

Speaking to the Masses

Charles Spurgeon came to London as a mere lad, and no preacher received more criticism than the 19-year-old “boy preacher,” as he was called. Becoming pastor of the historic New Park Street Baptist Church, he found the press virtually at war with him. The Ipswich Express said his sermons were “Redolent of bad taste, vulgar, and theatrical.”

Spurgeon replied, “I am perhaps vulgar, but it is not intentional, save that I must and will make the people listen. My firm conviction is that we have had quite enough polite preachers, and many require a change. God has owned me among the most degraded and off-casts. Let others serve their class; these are mine, and to them I must keep.”

Spurgeon saw the value of preaching to the common people in their own language and in a way that captivated their interest. He well understood the sophistication of the Established Church and its irrelevance to his own social setting. One editorial cartoon depicted an Anglican rector driving an old stagecoach with two slow horses—named “Church” and “State.” Racing ahead, however, is a young preacher with flowing hair, speeding on a locomotive engine. The title of the second cleric’s locomotive? “The Spurgeon,” of course.

Even British evangelicalism tended to be an upper-middle-class institution. With his “vulgar” style, however, Spurgeon spoke to the people of the street. Actually, Spurgeon’s church became known as a “church of shopkeepers,” but the criticism still mounted. Spurgeon finally said in exasperation, “Scarcely a Baptist minister of standing will own me.” But multitudes came to hear him preach.

It would not be fair to say that Spurgeon was the only evangelical preacher who took this approach and was criticized for it. Yet Spurgeon was the most successful in preaching to the common culture. When Spurgeon was 20 years old, he wrote to his future wife, Susannah Thompson, about an open-air sermon to a multitude: “Yesterday I climbed to the summit of a minister’s glory … the Lord was with me, and the profoundest silence was observed; but oh, the closeness—never did mortal man receive a more enthusiastic ovation! I wonder that I am alive!… Thousands of heads and hands were lifted, and cheer after cheer was given. Surely amid these adulations I can hear the low rumbling of the advancing storm of reproach. But even this I can bear for the Master’s sake.”

When it came to declaring the gospel in a relevant fashion to the common masses, Spurgeon was a master. He was a nineteenth-century reflection of George Whitefield.

An editorial cartoon that likened Spurgeon’s

preaching to the new steam engines: exciting and risky,

but infinitely superior to the old mode of transportation.

Focusing on

Christ

Spurgeon once described his approach to preaching by saying, “I take my text and make a bee-line to the cross.” He burned with a desire to preach the Good News and see people won to faith in Jesus Christ. Spurgeon declared that “Saving faith is an immediate relation to Christ, accepting, receiving, resting upon Him alone, for justification, sanctification, and eternal life by virtue of the covenant of grace.” He fervently urged people to enter into this faith relationship.

What may seem paradoxical to some today is that theologically, Spurgeon tenaciously clung to traditional Calvinism. Evangelistic appeals came from this preacher who adhered to the traditional five doctrinal points of the Synod of Dort, including unconditional election.

Spurgeon was once asked how he could reconcile his stance between Calvinistic theology and his fervent preaching of the gospel. He replied, “I do not try to reconcile friends.”

Spurgeon stood on the precarious razor’s edge between High Calvinism and Arminianism and preached the Word of God as he understood it. Thus, The World Newspaper reported that “Mr. Spurgeon is nominally a Calvinist.” He was rejected by many of the high Calvinistic churches. The pastor of the Surrey Chapel, for example, spent time every Sunday criticizing Spurgeon’s previous sermon because it was not Calvinistic enough. At the same time, Spurgeon was certainly not admitted to Arminian circles because he was far too Calvinistic for them.

Why this paradox? Spurgeon preached what he found in the Word of God and was not overly concerned to systematize everything. A reading of just a scattering of his sermons makes it obvious that when Spurgeon took a text, he took it seriously. And he used it to point people to Christ—not to establish or reestablish a formal doctrinal system.

Developing

Dramatic Gifts

Spurgeon was endowed with a beautiful speaking voice—it had melody, depth, and a resonance that could be heard by many thousands of people. Yet he never seemed to be straining.

He also had a dramatic flair and style that was captivating. The manager of London’s Drury Lane Theater said, “I would give a large amount of money if I could get Spurgeon on the stage.” Not that Spurgeon was superficially theatrical; it was his real self that gave him such a dramatic style in his preaching.

Spurgeon also had an eloquence that gives the impression he labored hours over his similes, metaphors, and dramatic illustrations. Yet he prepared his Sunday morning sermon Saturday night, and his Sunday night sermon on Sunday afternoon. He would walk into the pulpit with a simple, small outline, sometimes written on the back of an envelope, and from that extemporaneously pour forth eloquence almost equal to Shakespeare’s.

At the same time, it is only fair to say that Spurgeon studied diligently and read avidly. He amassed a personal library of over twelve thousand volumes, and he had a virtually photographic memory to call up his hours of study when he needed them in the pulpit.

Spurgeon’s notes for a sermon on Luke 2:10–12+.

Notice his three point outline and constant use of parallelism.

Bringing

Innovations

The question is raised, Was Spurgeon an innovator in his preaching?

Spurgeon broke with tradition and convention; he would not preach stilted sermons. As pointed out he spoke in common language to common people—in a dramatic, eloquent, even humorous way. He painted word pictures.

If there was “newness” about Spurgeon’s method, it was that he strove to be a communicator. Spurgeon never forgot that if a preacher fails to communicate—regardless of ability, sincerity, theology or natural gifts—a preacher has failed. So he addressed people where they were and spoke simply to their deepest needs. That is innovation at its best and would make a preacher effective in any age.

Drawing on

a Deep Spirituality

Foremost of all, Spurgeon was a man of God. The depth and breadth of his spirituality was profound. He quoted medieval mystics as well as John Law, John Wesley, and other spiritual giants of European Christianity. He was devoted to prayer.

Here is the powerhouse

of this church.

When people would walk through the Metropolitan Tabernacle (as New Park Street Church became known), Spurgeon would take them to a basement prayer room where people were always on their knees interceding for the church. Then the pastor would declare, “Here is the powerhouse of this church.”

Devoted to the Scriptures, to disciplined prayer, and to godly living, Spurgeon exemplified Christian commitment when he stood in the pulpit. This itself gave power to his preaching.

The One Thing

He Lacked

Perhaps it is correct to say that as a preacher, Spurgeon had everything—except good health. He suffered constantly from various ailments and fell into serious depression at times. He had rheumatic gout that eventually took his life at the age of 57.

Yet Spurgeon overcame physical limitations and relentless criticism to be established as the greatest Victorian preacher. He went to New Park Street Baptist Church as a teenager and on his first Sunday preached to eighty people. Yet during his thirty-seven years of ministry there, the congregation grew to become the largest evangelical church in the world.

When one considers Spurgeon’s great heart, biblical exposition of the gospel, cultural relevance, dramatic flair, and eloquence, it’s little wonder he took the country by storm.

He preached a relevant gospel in such a way that common people heard him gladly. This is the essence of great preaching, and it was the genius of Charles Haddon Spurgeon.

It was the first Sunday of the New Year, and this was how it opened ! On roads and footpaths the snow was already many inches deep; the fields were a sheet of blinding whiteness; and the flakes were still falling as though they never meant to stop. As the caretaker fought his way through the storm from his cottage to the chapel in Artillery Street, he wondered whether, on such a wild and wintry day, anyone would venture out. It would be strange if, on the very first Sunday morning of the year, there should be no service. He unbolted the chapel doors and lit the furnace under the stove. Half an hour later, two men were seen bravely trudging their way through the snowdrifts; and, as they stood on the chapel steps, their faces flushed with their recent exertions, they laughingly shook the snow from off their hats and overcoats. What a morning, to be sure! By eleven o'clock about a dozen others had arrived; but where was the minister? They waited; but he did not come. He lived at a distance, and, in all probability, had found the roads impassable. What was to be done? The stewards looked at each other and surveyed the congregation. Except for a boy of fifteen sitting under the gallery, every face was known to them, and the range of selection was not great. There were whisperings and hasty consultations, and at last one of the two men who were first to arrive—`a poor, thin-looking man, a shoemaker, a tailor, or something of that sort'—yielded to the murmured entreaties of the others and mounted the pulpit steps. He glanced nervously round upon nearly three hundred empty seats. Nearly, but not quite! For there were a dozen or fifteen of the regular worshippers present, and there was the boy sitting under the gallery. People who had braved such a morning deserved all the help that he could give them, and the strange boy under the gallery ought not to be sent back into the storm feeling that there was nothing in the service for him. And so the preacher determined to make the most of his opportunity ; and he did.

The boy sitting under the gallery! A marble tablet now adorns the wall near the seat which he occupied that snowy day. The inscription records that, that very morning, the boy sitting under the gallery was converted ! He was only fifteen, and he died at fifty-seven. But, in the course of the intervening years, he preached the gospel to millions and led thousands and thousands into the kingdom and service of Jesus Christ. 'Let preachers study this story!' says Sir William Robertson Nicoll. 'Let them believe that, under the most adverse circumstances, they may do a work that will tell on the universe forever. It was a great thing to have converted Charles Haddon Spurgeon; and who knows but he may have in the smallest and humblest congregation in the world some lad as well worth converting as was he ?'

II Snow! Snow! Snow!

The boy sitting under the gallery had purposed attending quite another place of worship that Sunday morning. No thought of the little chapel in Artillery Street occurred to him as he strode out into the storm. Not that he was very particular. Ever since he was ten years of age he had felt restless and ill at ease whenever his mind turned to the things that are unseen and eternal. 'I had been about five years in the most fearful distress of mind,' he says. 'I thought the sun was blotted out of my sky, that I had so sinned against God that there was no hope for me!' He prayed, but never had a glimpse of an answer. He attended every place of worship in the town; but no man had a message for a youth who only wanted to know what he must do to be saved. With the first Sunday of the New Year he purposed yet another of these ecclesiastical experiments. But in making his plans he had not reckoned on the ferocity of the storm. 'I sometimes think,' he said, years afterwards, 'I sometimes think I might have been in darkness and despair now, had it not been for the goodness of God in sending a snowstorm on Sunday morning, January 6th, 185o, when I was going to a place of worship. When I could go no further I turned down a court and came to a little Primitive Methodist chapel.' Thus the strange boy sitting under the gallery came to be seen by the impromptu speaker that snowy morning! Thus, as so often happens, a broken program pointed the path of destiny ! Who says that two wrongs can never make a right? Let them look at this ! The plans at the chapel went wrong; the minister was snowed up. The plans of the boy under the gallery went wrong: the snowstorm shut him off from the church of his choice. Those two wrongs together made one tremendous right; for out of those shattered plans and programmes came an event that has incalculably enriched mankind.

III Snow! Snow! Snow!

And the very snow seemed to mock his misery. It taunted him as he walked to church that morning. Each virgin snowflake as it fluttered before his face and fell at his feet only emphasised the dreadful pollution within. 'My original and inward pollution!' he cries with Bunyan ; 'I was more loathsome in mine own eyes than a toad. Sin and corruption would as naturally bubble out of my heart as water out of a fountain. I thought that everyone had a better heart than I had. At the sight of my own vileness I fell deeply into despair.' These words of Bunyan's exactly reflect, he tells us, his own secret and spiritual history. And the white, white snow only intensified the agonizing consciousness of defilement. In the expressive phraseology of the Church of England Communion Service, 'the remembrance of his sins was grievous unto him; the burden of them was intolerable.' I counted the estate of everything that God had made far better than this dreadful state of mind was : yea, gladly would I have been in the condition of a dog or a horse ; for I knew they had no souls to perish under the weight of sin as mine was like to do.' Many and many a time,' says Mr. Thomas Spurgeon, 'my father told me that, in those early days, he was so storm tossed and distressed by reason of his sins that he found himself envying the very beasts in the field and the toads by the wayside !' So storm tossed! The storm that raged around him that January morning was in perfect keeping with the storm within ; but oh, for the whiteness, the pure, unsullied whiteness, of the falling snow I

IV Snow! Snow! Snow!

From out of that taunting panorama of purity the boy passed into the cavernous gloom of the almost empty building. Its leaden heaviness matched the mood of his spirit, and he stole furtively to a seat under the gallery. He noticed the long pause; the anxious glances which the stewards exchanged with each other; and, a little later, the whispered consultations. He watched curiously as the hastily-appointed preacher—`a shoemaker or something of that sore—awkwardly ascended the pulpit. 'The man was,' Mr. Spurgeon tells us, 'really stupid as you would say. He was obliged to stick to his text for the simple reason that he had nothing else to say. His text was, "Look unto Me and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth." (Isaiah 45:22) He did not even pronounce the words rightly, but that did not matter. There was, I thought, a glimpse of hope for me in the text, and I listened as though my life depended upon what I heard. In about ten minutes the preacher had got to the end of his tether. Then he saw me sitting under the gallery; and I daresay, with so few present, he knew me to be a stranger. He then said : "Young man, you look very miserable." Well, I did; but I had not been accustomed to have remarks made from the pulpit on my personal appearance. However, it was a good blow, well struck. He continued : "And you will always be miserable—miserable in life, and miserable in death—if you do not obey my text. But if you obey now, this moment, you will be saved !" Then he shouted, as only a Primitive Methodist can shout, "Young man, look to Jesus! look, look, look!" I did; and, then and there, the cloud was gone, the darkness had rolled away, and that moment I saw the sun! I could have risen on the instant and sung with the most enthusiastic of them of the precious blood of Christ and of the simple faith which looks alone to Him. Oh, that somebody had told me before! In their own earnest way, they sang a Hallelujah before they went home, and I joined in it !'

The snow around!

The defilement within!

Look unto Me and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth!'

Precious blood . . . and simple faith!' `I sang a Hallelujah!'

V Snow ! Snow! Snow!

The snow was falling as fast as ever when the boy sitting under the gallery rose and left the building. The storm raged just as fiercely. And yet the snow was not the same snow ! Everything was changed. Mr. Moody has told us that, on the day of his conversion, all the birds in the hedgerow seemed to be singing newer and blither songs. Dr. Campbell Morgan declares that the very leaves on the trees appeared to him more beautiful on the day that witnessed the greatest spiritual crisis in his career. Frank Bullen was led to Christ in a little New Zealand port which I have often visited, by a worker whom I knew well. And he used to say that, next morning, he climbed the summit of a mountain near by and the whole landscape seemed changed. Everything had been transformed in the night !

Heaven above is softer blue,

Earth around a deeper green,

Something lives in every hue

Christless eyes have never seen.

Birds with gladder songs o'erflow,

Flowers with richer beauties shine,

Since I know, as now I know,

I am His and He is mine!

`I was now so taken with the love of God,' says Bunyan—and here again Mr. Spurgeon says that the words might have been his own--`I was now so taken with the love and mercy of God that I could not tell how to contain till I got home. I thought I could have spoken of His love, and told of His mercy, even to the very crows that sat upon the ploughed lands before me, had they been capable of understanding me.' As the boy from under the gallery walked home that morning he laughed at the storm, and the snow that had mocked him coming sang to him as he returned. 'The snow was lying deep,' he says, 'and more was falling. But those words of David kept ringing through my heart, "Wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow!" It seemed to me as if all Nature was in accord with the blessed deliverance from sin which I had found in a moment by looking to Jesus Christ!'

The mockery of the snow!

The text amidst the snow!

The music of the snow!

Whiter than the snow!

`Look unto Me and be ye saved!'

`Wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow!'

VI `Look unto ME and be ye saved!' Look! Look! Look!

I look to my doctor to heal me when I am hurt; I look to my lawyer to advise me when I am perplexed; I look to my tradesmen to bring my daily supplies to my door; but there is only One to whom I can look when my soul cries out for deliverance.

`Look unto Me and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth!'

`Look! Look! Look!' cried the preacher.

'I looked,' says Mr. Spurgeon, 'until I could almost have looked my eyes away; and in heaven I will look still, in joy unutterable !'

Happy the preacher, however unlettered, who, knowing little else, knows how to direct such wistful and hungry eyes to the only possible fountain of sat-is faction!

"Snow, Snow, Snow" is from Frank Boreham's fascinating book entitled A Bunch of Everlastings -

This is a fascinating book in which Boreham describes the role of a text from the Bible which was instrumental in bringing 23 well known saints to salvation (e.g., Martin Luther, John Knox, John Bunyan, David Livingstone, William Carey, John Wesley, John Newton, et al). Click here for the table of contents and take some time to read how God's Word moved in mysterious ways to redeem each of these dead souls from darkness to eternal light and life in Christ Jesus our Lord. I can assure you that your faith will be strengthened and encouraged as you see God's mighty hand of providence. What an awesome God we serve...

Wherefore He is able also to save them to the uttermost that come unto God by him,

seeing he ever liveth to make intercession for them.

Hebrews 7:25KJV+

Spurgeon's Devotional - Faith's Checkbook

Spurgeon's Devotional - Morning and Evening

Feathers for Arrows - Compilation of Illustrations

Spurgeon on the Attributes of God

Spurgeon on Daniel - Devotionals

Spurgeon on the Psalms - Sermons and Devotionals Indexed by Scripture

Spurgeon on the Psalms - Part 1 - Full Devotionals from Morning and Evening Indexed by Scripture

Spurgeon on the Psalms - Part 2 - Full Devotionals from Morning and Evening Indexed by Scripture