Published 1884 - George N H. Peters (November 30, 1825-October 7, 1909) "was an American Lutheran minister and author of The Theocratic Kingdom. His premillennial views were in conflict with the majority of Lutherans who held amillennial beliefs.[1][2]

“Buy the truth and sell it not; also wisdom, and instruction, and understanding.”—Pr 23:23.

“The secret of the Lord is with them that fear Him; and He will show them His covenant.”—Ps. 25:14.

NOTE: This is Volume 1 of this massive 2189 page work, all written before the typewriter was invented! This is the quintessential epitome of a person's "life work!"

INDEX:

- Volume 1 - Propositions 1 - 106

- Volume 2 - Propositions 107 - 164

- Volume 3 - Propositions 165 - 206

- Index of Scriptures & Subjects

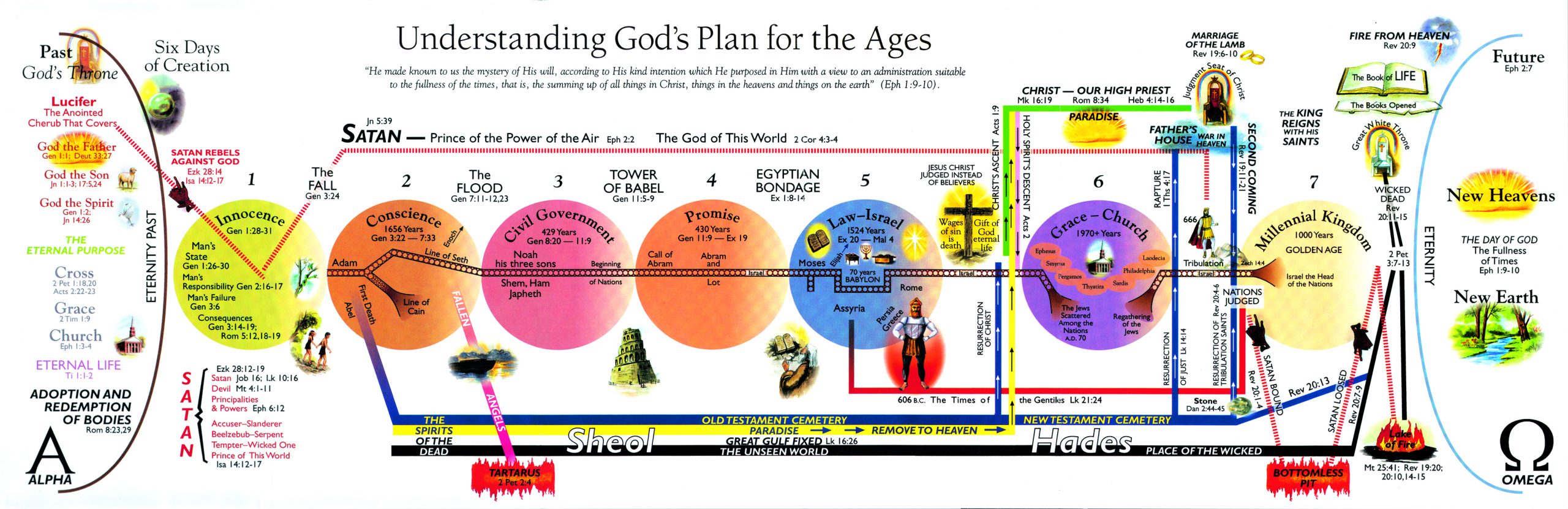

Source: Chart by Tim LaHaye and Thomas Ice - click to enlarge - Millenium on Right Side

Excerpt from Peter's biography - George Peters is remembered primarily because of his three volume work The Theocratic Kingdom of Our Lord Jesus, the Christ, as Covenanted in the Old Testament and Presented in the New Testament. The title is often shortened to simply The Theocratic Kingdom. His references indicate he was well read in theology, history, science and literature. He spent years researching and compiling this study of eschatology, which includes over four thousand quotes from authors ranging from the second century to his own era. The work was first published in 1884 by Funk and Wagnalls. (Isaac Kauffman Funk had graduated from Wittenberg College in 1860 and from its seminary in 1861.) Kregel republished The Theocratic Kingdom in 1952 and 1972, and it was still in print in May 2006. In his preface to the 1952 edition, Wilbur M. Smith wrote “One does not need to agree with all of his [Peters’] statements, nor even with all of his interpretations, to recognize the greatness of this work that must have cost him a lifetime of research, prayer, investigation, and laborious writing – these were the days before typewriters.” Surviving manuscripts indicate Peters wrote many books, but The Theocratic Kingdom may have been the only one published, because that is the only title by Peters in bibliographic records in WorldCat. On the handwritten title page of an unpublished work, Peters described himself as an “evangelical Lutheran Minister.” (Source)

- PROPOSITION 1.—The Kingdom of God is a subject of vital importance

- PROP. 2.—The establishment of this Kingdom was determined before, and designed or prepared from, the foundation of the world

- PROP. 3.—The meanings usually given to this Kingdom indicate that the most vague, indefinite notions concerning it exist in the minds of many

- PROP. 4.—The literal, grammatical interpretation of the Scriptures must (connected with the figurative, tropical, or rhetorical) be observed in order to obtain a correct understanding of the Kingdom

- PROP. 5.—The doctrine of the Kingdom is based on the inspiration of the Word of God

- PROP. 6.—The Kingdom of God is intimately connected with the Supernatural

- PROP. 7.—The Kingdom being a manifestation of the Supernatural, miracles are connected with it

- PROP. 8.—The doctrine of the Kingdom presupposes that of sin, the apostasy of man

- PROP. 9.—The nature of, and the things pertaining to, the Kingdom can only be ascertained within the limits of Scripture

- PROP. 10.—This Kingdom should be studied in the light of the Holy Scriptures, and not merely in that of Creeds, Confessions, Formulas of Doctrine, etc.

- PROP. 11.—The mysteries of the Kingdom were given to the apostles

- PROP. 12.—There is some mystery yet connected with the things of the Kingdom

- PROP. 13.—Some things pertaining to the Kingdom intentionally revealed somewhat obscurely

- PROP. 14.—Some things pertaining to the Kingdom not so easily comprehended as many suppose

- PROP. 15.—The doctrine of the Kingdom can become better understood and appreciated

- PROP. 16.—This Kingdom cannot be properly comprehended without acknowledging an intimate and internal connection existing between the Old and New Testaments

- PROP. 17.—Without study of the prophecies no adequate idea can be obtained of the Kingdom

- PROP. 18.—The prophecies relating to the establishment of the Kingdom of God are both conditioned and unconditioned

- PROP. 19.—The New Testament begins the announcement of the Kingdom in terms expressive of its being previously well known

- PROP. 20.—To comprehend the subject of the Kingdom it is necessary to notice the belief and expectations of the more pious portion of the Jews

- PROP. 21.—The prophecies of the Kingdom interpreted literally sustain the expectations and hopes of the pious Jews

- PROP. 22.—John the Baptist, Jesus, and the disciples employed the phrases “Kingdom of Heaven,” “Kingdom of God,” etc., in accordance with the usage of the Jews

- PROP. 23.—There must be some substantial reason why the phrases “Kingdom of God,” etc., were thus adopted

- PROP. 24.—The Kingdom is offered to an elect nation, viz., the Jewish nation

- PROP. 25.—The Theocracy was an earnest, introductory, or initiatory form of this Kingdom

- PROP. 26.—The Theocracy thus instituted would have been permanently established if the people, in their national capacity, had been faithful in obedience

- PROP. 27.—The demand of the nation for an earthly king was a virtual abandonment of the Theocratic Kingdom by the nation

- PROP. 28.—God makes the Jewish king subordinate to His own Theocracy

- PROP. 29.—This Theocracy, or Kingdom, is exclusively given to the natural descendants of Abraham, in their corporate capacity

- PROP. 30.—The prophets, however, without specifying the manner of introduction, predict that the Gentiles shall participate in the blessings of the Theocracy or Kingdom

- PROP. 31.—This Theocracy was identified with the Davidic Kingdom

- PROP. 32.—This Theocratic Kingdom, thus incorporated with the Davidic, is removed when the Davidic is overthrown

- PROP. 33.—The prophets, some even before the captivity, foreseeing the overthrow of the Kingdom, both foretell its downfall and its final restoration

- PROP. 34.—The prophets describe this restored Kingdom, its extension, glory, etc., without distinguishing between the First and Second Advents

- PROP. 35.—The prophets describe but one Kingdom

- PROP. 36.—The prophets, with one voice, describe this one Kingdom, thus restored, in terms expressive of the most glorious additions

- PROP. 37.—The Kingdom thus predicted and promised was not in existence when the forerunner of Jesus appeared

- PROP. 38.—John the Baptist preached that this Kingdom, predicted by the prophets, was “nigh at hand”

- PROP. 39.—John the Baptist was not ignorant of the Kingdom that he preached

- PROP. 40.—The hearers of John believed that he preached to them the Kingdom predicted by the prophets, and in the sense held by themselves

- PROP. 41.—The Kingdom was not established under John’s ministry

- PROP. 42.—Jesus Christ in His early ministry preached that the Kingdom was “nigh at hand”

- PROP. 43.—The disciples sent forth by Jesus to preach this Kingdom were not ignorant of the meaning to be attached to the Kingdom

- PROP. 44.—The preaching of the Kingdom, being in accordance with that of the predicted Kingdom, raised no controversy between the Jews and Jesus, or between the Jews and His disciples and apostles

- PROP. 45.—The phrases “Kingdom of Heaven,” “Kingdom of God,” “Kingdom of Christ,” etc., denote the same Kingdom

- PROP. 46.—The Kingdom anticipated by the Jews at the First Advent is based on the Abrahamic and Davidic covenants

- PROP. 47.—The Jews had the strongest possible assurances given to them that the Kingdom based on these covenants would be realized

- PROP. 48.—The Kingdom being based on the covenants, the covenants must be carefully examined, and (PROP. 4) the literal language of the same must be maintained

- PROP. 49.—The covenants being, in Revelation, the foundation of the Kingdom, must first be received and appreciated

- PROP. 50.—This Kingdom will be the outgrowth of the renewed Abrahamic covenant, under which renewal we live

- PROP. 51.—The relation that the Kingdom sustains to “the covenants of promise” enables us to appreciate the prophecies pertaining to the Kingdom

- PROP. 52.—The promises pertaining to the Kingdom, as given in the covenants, will be strictly fulfilled

- PROP. 53.—The genealogies of our Lord form an important link in the comprehension of the Kingdom

- PROP. 54.—The preaching of the Kingdom by John, Jesus, and the disciples, was confined to the Jewish nation

- PROP. 55.—It was necessary that Jesus and His disciples should, at first, preach the Kingdom as nigh to the Jewish nation

- PROP. 56.—The Kingdom was not established during the ministry of “the Christ”

- PROP. 57.—This Kingdom was offered to the Jewish nation, but the nation rejected it

- PROP. 58.—Jesus, toward the close of His ministry, preached that the Kingdom was not nigh

- PROP. 59.—This Kingdom of God offered to the Jewish elect nation, lest the purpose of God fail, is to be given to others who are adopted

- PROP. 60.—This Kingdom of God is given, not to nations, but to one nation

- PROP. 61.—The Kingdom which by promise exclusively belonged to the Jewish nation, the rightful seed of Abraham, was now to be given to an engrafted people

- PROP. 62.—This people, to whom the Kingdom is to be given, gathered out of the nations, becomes the elect nation

- PROP. 63.—The present elect, to whom the Kingdom will be given, is the continuation of the previous election chiefly in another engrafted people

- PROP. 64.—The Kingdom being given to the elect only, any adoption into that elect portion must be revealed by express Divine Revelation

- PROP. 65.—Before this Kingdom can be given to this elect people, they must first be gathered out

- PROP. 66.—The Kingdom that was nigh at one time (viz., at the First Advent) to the Jewish nation is now removed to the close of its tribulation, and of the times of the Gentiles

- PROP. 67.—The Kingdom could not, therefore, have been set up at that time, viz., at the First Advent

- PROP. 68.—This Kingdom is then essentially a Jewish Kingdom

- PROP. 69.—The death of Jesus did not remove the notion entertained by the disciples and apostles concerning the Kingdom

- PROP. 70.—The apostles, after Christ’s ascension, did not preach, either to Jews or Gentiles, that the Kingdom was established

- PROP. 71.—The language of the apostles confirmed the Jews in their Messianic hopes of the Kingdom

- PROP. 72.—The doctrine of the Kingdom, as preached by the apostles, was received by the early Church

- PROP. 73.—The doctrine of the Kingdom preached by the apostles and elders raised up no controversy with the Jews

- PROP. 74.—The belief in the speedy Advent of Christ, entertained both by the apostles and the churches under them, indicates what Kingdom was believed in and taught by the first Christians

- PROP. 75.—The doctrine of the Kingdom, as held by the churches established by the apostles, was perpetuated

- PROP. 76.—The doctrine of the Kingdom was changed under the Gnostic and Alexandrian influence

- PROP. 77.—The doctrine of the Kingdom, as held by the early Church, was finally almost exterminated under the teaching and power of the Papacy

- PROP. 78.—The early Church doctrine was revived after the Reformation

- PROP. 79.—The Kingdom of God, promised by covenant and prophets, is to be distinguished from the general and universal sovereignty of God

- PROP. 80.—This Kingdom of covenant, promise, and prediction is to be distinguished from the sovereignty which Jesus exercises in virtue of His Divine nature

- PROP. 81.—This Kingdom, as covenanted, belongs to Jesus, as “the Son of Man”

- PROP. 82.—This Kingdom is a complete restoration, in the person of the Second Adam or Man, of the dominion lost by the First Adam or Man

- PROP. 83.—This Kingdom is given to “the Son of Man” by God, the Father

- PROP. 84.—As this Kingdom is specially given to “the Son of Man” as the result of His obedience, sufferings, and death, it must be something different from His Divine nature, or from “piety,” “religion,” “God’s reign in the heart,” etc.

- PROP. 85.—Neither Abraham nor his engrafted seed have as yet inherited the Kingdom; hence the Kingdom must be something different from “piety,” “religion,” “God’s reign in the heart,” etc.

- PROP. 86.—The object or design of this dispensation is to gather out these elect to whom, as heirs with Abraham and his seed Christ, this Kingdom is to be given

- PROP. 87.—The postponement of the Kingdom is the key to the understanding of the meaning of this dispensation

- PROP. 88.—The Church is then a preparatory stage for this Kingdom

- PROP. 89.—Christ, in view of this future Kingdom, sustains a peculiar relationship to the Church

- PROP. 90.—Members of the Church who are faithful are promised this Kingdom

- PROP. 91.—The Kingdom of God is not the Jewish Church

- PROP. 92.—This Kingdom is not what some call, “the Gospel Kingdom”

- PROP. 93.—The covenanted Kingdom is not the Christian Church

- PROP. 94.—The overlooking of the postponement of this Kingdom is a fundamental mistake and fruitful source of error in many systems of Theology

- PROP. 95.—If the Church is the Kingdom, then the terms “Church” and “Kingdom” should be synonymous

- PROP. 96.—The differences visible in the Church are evidences that it is not the predicted Kingdom of the Messiah

- PROP. 97.—The various forms of Church government indicate that the Church is not the promised Kingdom

- PROP. 98.—That the Church was not the Kingdom promised to David’s Son was the belief of the early Church

- PROP. 99.—The opinion that the Church is the predicted Kingdom of the Christ was of later origin than the first or second century

- PROP. 100.—The visible Church is not the predicted Kingdom of Jesus Christ

- PROP. 101.—The invisible Church is not the covenanted Kingdom of Christ

- PROP. 102.—Neither the visible nor invisible Church is the covenanted Kingdom

- PROP. 103.—This Kingdom is not a Kingdom in “the third heaven”

- PROP. 104.—The Christian Church is not denoted by the predicted Kingdom of the prophets

- PROP. 105.—The Lord’s Prayer, as given to the disciples, and understood by them, amply sustains our position

- PROP. 106.—Our doctrine of the Kingdom sustained by the temptation of Christ

- PROPOSITION 107.—The passages referring to heaven in connection with the saints, do not conflict with, but confirm, our doctrine of the Kingdom

- PROP. 108.—The formula, “Kingdom of heaven,” connected with the parables, confirms our doctrine of the Kingdom

- PROP. 109.—An examination of the passages of Scripture, supposed to teach the Church-Kingdom theory, will confirm our doctrine of the Kingdom

- PROP. 110.—The passage most relied on to prove the Church-Kingdom theory, utterly disproves it

- PROP. 111.—The Kingdom being identified with the elect Jewish nation, it cannot be established without the restoration of that nation

- PROP. 112.—The Kingdom, if established as predicted, demands the national restoration of the Jews to their own land

- PROP. 113.—The connection of this Kingdom with Jewish restoration necessitates the realization of their predicted repentance and conversion

- PROP. 114.—This Kingdom being identified with the elect Jewish nation, its establishment at the restoration embraces the supremacy of the nation over the nations of the earth

- PROP. 115.—The Kingdom is not established without a period of violence and war

- PROP. 116.—This Kingdom is a visible, external one, here on the earth, taking the place of earthly Kingdoms

- PROP. 117.—The Kingdom of God re-established, will form a divinely appointed, and visibly manifested, Theocracy

- PROP. 118.—This view of the Kingdom is most forcibly sustained by the figure of the Barren Woman

- PROP. 119.—The Kingdom of God is represented, in the Millennial descriptions, as restoring all the forfeited blessings

- PROP. 120.—This Kingdom, with its Millennial blessings, can only be introduced through the power of God in Christ Jesus

- PROP. 121.—This Kingdom, of necessity, requires a Pre-Millennial Personal Advent of Jesus, “the Christ”

- PROP. 122.—As “Son of Man,” David’s Son, Jesus inherits David’s throne and kingdom, and also the land of Palestine

- PROP. 123.—The Pre-Millennial Advent and accompanying Kingdom are united with the destruction of Antichrist

- PROP. 124.—This Kingdom is delayed several thousand years, to raise up a nation or people capable of sustaining it

- PROP. 125.—The Kingdom to be inherited by these gathered saints requires their resurrection from the dead

- PROP. 126.—In confirmation of our position, the Old Testament clearly teaches a Pre-Millennial resurrection of the saints

- PROP. 127.—In support of our view, the Apocalypse unmistakably teaches a Pre-Millennial resurrection of the saints

- PROP. 128.—The language of the Gospels and Epistles is in strict accord with the requirements of a Pre-Mill. resurrection

- PROP. 129.—The Jewish view of a Pre-Mill. resurrection, requisite for the introduction of the Messianic Kingdom, is fully sustained by the grammatical sense of the New Testament

- PROP. 130.—This Kingdom is also preceded by a translation of living saints

- PROP. 131.—This Kingdom embraces the visible reign of Jesus, the Christ, here on earth

- PROP. 132.—This view of the Kingdom confirmed by the judgeship of Jesus

- PROP. 133.—This view of the Kingdom fully sustained by the “Day of Judgment.”

- PROP. 134.—Our view of the Judgment (and, as a consequence, that also of the Kingdom) is fully sustained by the passage of Scripture, Matt. 25:31–46

- PROP. 135.—The doctrine of the Kingdom in full accord with the scriptural doctrine of the judgment of believers

- PROP. 136.—The doctrine of the Kingdom in agreement with the doctrine of the intermediate state

- PROP. 137.—This doctrine of the Kingdom sustained by the phrase “the world to come”

- PROP. 138.—This doctrine of the Kingdom fully corroborated by “the day of the Lord Jesus, the Christ”

- PROP. 139.—The Theocratic-Davidic Kingdom, as covenanted, is sustained by what is to take place in “the morning” of “the day of the Christ”

- PROP. 140.—The doctrine of the Kingdom confirmed by the phraseology of the New Testament respecting “the end of the age”

- PROP. 141.—This Kingdom necessarily united with the perpetuity of the earth

- PROP. 142.—The Kingdom being related to the earth (extending over it), and involving the resurrection of the saints (in order to inherit it), is sustained by the promise to the saints of inheriting the earth

- PROP. 143.—The early church doctrine of the Kingdom is supported by “the Rest,” or the keeping of the Sabbath, mentioned by Paul

- PROP. 144.—This Kingdom embraces “the times of refreshing,” and “the times of the restitution of all things,” mentioned Acts 3:19–21

- PROP. 145.—This Kingdom includes “the regeneration” of Matt. 19:28

- PROP. 146.—This Kingdom is associated with the deliverance of Creation

- PROP. 147.—This Kingdom is preceded by a wonderful shaking of the heavens and the earth

- PROP. 148.—This Kingdom embraces the New Heavens and New Earth

- PROP. 149.—This Kingdom is preceded by the conflagration of 2 Pet. 3:10–13

- PROP. 150.—The establishment of this Kingdom is not affected by the extent of Peter’s conflagration

- PROP. 151.—This Kingdom is identified with “the New Heavens and New Earth” of Isa. 65:17 and 66:22; 2 Pet. 3:13; and Rev. 21:1

- PROP. 152.—This Kingdom is connected with the perpetuation of the human race

- PROP. 153.—This view of the Kingdom, with its two classes (viz., the translated and resurrected saints, glorified, forming one class, and mortal men the other), is forcibly represented in the transfiguration

- PROP. 154.—This Theocratic Kingdom includes the visible reign of the risen and glorified saints, here on the earth

- PROP. 155.—This Kingdom exhibits Jesus not only as “the King,” but also as “the Priest”

- PROP. 156.—The doctrine of the Kingdom enforces the future priesthood of the saints

- PROP. 157.—This doctrine of the Kingdom enforces the future ministrations of angels

- PROP. 158.—The doctrine of the Kingdom aids in locating the Millennial period

- PROP. 159.—This Theocratic Kingdom of the Lord Jesus, the Christ, will never come to an end

- PROP. 160.—This Kingdom will be set up in the divided state of the Roman Empire

- PROP. 161.—This Kingdom will not be re-established until Antichrist is overthrown

- PROP. 162.—This Kingdom will be preceded by a fearful time of trouble, both in the Church and the world

- PROP. 163.—This Kingdom revealed will be preceded by the predicted “Battle of that great day of God Almighty”

- PROP. 164.—This Kingdom ends the Gentile domination

- PROP. 165.—The doctrine of this Kingdom enables us to form a correct estimate of human governments

- PROP. 166.—The rudimentary reorganization of the Kingdom will be made at Mount Sinai

- PROP. 167.—The re-establishment of this Kingdom embraces also the reception of a New Revelation of the Divine Will

- PROP. 168.—This Kingdom has its place of manifested royalty

- PROP. 169.—The Theocratic Kingdom includes the marriage of Christ to the New Jerusalem

- PROP. 170.—This doctrine of the Kingdom fully sustained by “the Father’s house” of John 14:2

- PROP. 171.—This Kingdom is connected with the Baptism of the Holy Ghost (Spirit) and of Fire.

- PROP. 172.—This Kingdom, when restored, does not require the re-introduction of bloody sacrifices

- PROP. 173.—The Kingdom of the Lord Jesus may be near at hand

- PROP. 174.—This Kingdom of the Messiah is preceded by, and connected with, signs

- PROP. 175.—The doctrine of the Kingdom is greatly obscured and perverted by the prevailing one of the conversion of the world prior to the Advent of Jesus

- PROP. 176.—Our doctrine of the Kingdom embraces the conversion of the world, but in the Scriptural order

- PROP. 177.—This doctrine of the Kingdom will not be received in faith by the Church, as a body

- PROP. 178.—This doctrine of the Kingdom, and its essentially related subjects, are so hostile to their faith, that numerous organized religious bodies totally reject them

- PROP. 179.—The doctrine of the Kingdom, or essentials of the same, are directly allied by various bodies with doctrines that are objectionable, and hence are made unpalatable to many

- PROP. 180.—This doctrine of the Kingdom will not be received in faith by the world

- PROP. 181.—Our doctrinal position illustrated and enforced by the Parable of the Ten Virgins

- PROP. 182.—This Kingdom embraces “the One Hope”

- PROP. 183.—The doctrine of the Kingdom, and its related subjects, have a direct practical tendency

- PROP. 184.—In this Kingdom will be exhibited a manifested unity

- PROP. 185.—This doctrine enforces that of Divine Providence

- PROP. 186.—This doctrine of the Kingdom sustained by the Analogy of Scripture, the Analogy of Faith, and the Analogy of Tradition

- PROP. 187.—This doctrine of the Kingdom gives coherency to the Gospels, and indicates the unity of design in each of them

- PROP. 188.—This doctrine indicates the unity of the Epistles

- PROP. 189.—It is only through this doctrine of the Kingdom that the Apocalypse can, or will, be understood and consistently interpreted

- PROP. 190.—Our views sustained by the addresses to the Seven Churches

- PROP. 191.—Our doctrine enforced by the general tenor of the Apocalypse

- PROP. 192.—This doctrine of the Kingdom greatly serves to explain Scripture

- PROP. 193.—This doctrine of the Kingdom meets, and consistently removes, the objections brought by the Jews against Christianity

- PROP. 194.—This doctrine of the Kingdom materially aids to explain the world’s history

- PROP. 195.—This doctrine of the Kingdom may, analogically, give us a clew to the government of other worlds

- PROP. 196.—This doctrine of the Kingdom gives us a more comprehensive view of the work of Christ for Redemptive purposes

- PROP. 197.—This Kingdom, although visible with a world-dominion, being Theocratic, is also necessarily spiritual

- PROP. 198.—The doctrine of the Kingdom confirms the credibility and inspiration of the Word of God

- PROP. 199.—This doctrine of the Kingdom materially aids in deciding the great Christological question of the day

- PROP. 200.—While the Kingdom is given to Jesus Christ as “the Son of Man,” He becomes thereby the actual Representative of God, manifesting God in the person of One related to humanity

- PROP. 201.—If a Kingdom such as is covenanted to “the Son of Man,” David’s Son, is not set up, then God’s effort at government, in and through an earthly rulership, proves a failure

- PROP. 202.—If the Kingdom of “the Son of Man,” as covenanted, is not established, then the earth will lack in its history the exhibition of a perfect government

- PROP. 203.—The exaltation of the Christ is not lessened or lowered by thus referring the promises of the Kingdom to an outward manifestation in the future

- PROP. 204.—Such a view gives definiteness and a continued exaltation to the human nature of Christ, and indicates the majestic relationship that it sustains throughout the ages to the race of man

- PROP. 205.—The doctrine of the Kingdom materially aids us in preaching “the Christ,” the distinctive “Messiah”

- PROP. 206.—This earth will yet witness the re-establishment of a glorious Theocracy—a Theocracy in its perfected form

- CONCLUSION

In this work it is proposed to show what the Covenants demand, and what relationship the second coming, kingdom, and glory of “The Christ” sustains to the same, in order that perfected Redemption may be realized. This, logically, introduces a large amount of converging testimony.

The history of the human race is, as able theologians have remarked, the history of God’s dealings with man. It is a fulfilling of revelation; yea, more: it is an unfolding of the ways of God, a comprehensive confirmation of, and an appointed aid in interpreting the plan of redemption. Hence God himself appeals to it, not merely as the evidence of the truth declared, but as the mode by which we alone can obtain a full and complete view of the Divine purpose relating to salvation. To do this we must, however, regard past, present, and future history. The latter must be received as predicted, for we may rest assured, from the past and present fulfillment of the word of God, thus changed into historical reality, that the predictions and promises relating to the future will also in their turn become veritable history. It is this faith, which grasps the future as already present, that can form a decided and unmistakable unity.

This is becoming more profoundly felt and expressed, and is forcibly portrayed in some recent publications (e.g., Dorner’s His. Prot. Theol., Auberlen’s Div. Rev., etc.). Seeing that all things are tending toward the kingdom to be hereafter established by Christ, that the dispensations from Adam to the present are only preparatory stages for its coming manifestation, surely it is the highest wisdom to direct special and careful attention to the kingdom itself. If it is the end which serves to explain the means employed; if it is the object for which ages have passed by and are ever to revolve; if the coming of Jesus, which is to inaugurate it, is emphatically called “the blessed hope;” if it embraces the culmination of the world’s history in ample deliverance and desired restitution; then it is utterly impossible for us to determine the true significance, the Divine course, and the development of the plan of salvation without a deep insight into that of the kingdom itself. Prophets, apostles, and Jesus himself, especially in his last testimony, continually point the eye of faith and the heart of hope to this kingdom as the bright light which can clearly illumine the past and present, and even dispel the darkness of the future. Scripture and theology, the latter in its very early and later development, teach us, if we will but receive it, that we cannot properly comprehend the Divine economy in its relation to man and the world, unless we reverently consider the manifestation of its ultimate result as exhibited in this kingdom. It follows, therefore, that a work of this kind, intended to give an understanding of a subject so vital, however defective in part, requires no apology to the reflecting mind. Every effort in this direction, if it evinces appreciation of truth and reverence for the word, will be received with pleasure by the true Biblical student.

In the reaction against Rationalism, Spiritualism, Naturalism, etc., special attention has been paid to the kingdom of God and the relation that it sustains to history. The attack and defense revealed both how important the subject, and how sadly it had been neglected. It has been admitted by recent writers of ability (e.g., Dr. Auberlen, Div. Rev., p. 387), that much is yet to be learned in reference to it; that only a beginning has been made in investigating the subject; that a correct solution of the difficulties surrounding it in order to give a satisfactory reply to objections is still a work of the future. Some (as e.g., Rothe), when looking over the great array of Biblical authors, still find in their labors a something lacking, which when carefully analyzed resolves itself in a lack of Divine unity in reference to the kingdom of God, evincing itself in a mystical, if not arbitrary, definition of it, in various forms, to suit a present exigency, or harmonize a supposed difficulty. This feeling is strengthened by the continued assaults of unbelievers, which have been for some time made against the early history of Christianity. Numerous works have appeared, and with the boldest criticism have pointed out discrepancies existing between the ancient faith and that entertained by the large body of the Church at the present day; and from such differences of belief have inferred that the early faith was sadly defective, and that its promulgators are therefore unworthy of our confidence. We are told that the apostles, apostolic fathers, and the first Christians generally were well-meaning and even noble men, but “ignorant, enthusiastic, and fanatical” in their opinions. Rejoinders, on the other hand, have appeared, which, professing to defend the apostles, and fathers, are yet forced, most unwillingly, to admit the leading charge preferred by their opponents. Thus, e.g., the German Rationalists point to the preaching of John the Baptist, the disciples, and the first believers, and show conclusively that they preached a kingdom which accorded with the Jewish forms—viz., a kingdom here on earth under the personal reign of the Messiah, the Davidic throne and kingdom being restored. They press this matter with an exultant feeling, realizing that the great proportion of the Church being opposed to such a belief materially aids them in condemning the first preaching of the gospel of the kingdom, and thus making the founders of the Church unworthy of credence. The Church itself, by its published faith respecting the kingdom, forges the weapons that are employed against it. Every work on the other side in defense of the founders of the Christian Church, unable to set aside the abundant and overwhelming evidence adduced, frankly admits that the first preaching was in a Jewish form; that the faith of the early Church is not now the faith of the Church (saving that of a few individuals); and endeavors to solve the difficulty (as, e.g., Neander, and others) by declaring, that the early period was a transition state, a preparatory stage, an adaptation to meet the necessities of that age; that hence the truth in the matter of the kingdom was enveloped in a “husk,” and was to be gradually evolved in “the consciousness of the Church” by its growth. Aside from thus virtually making Church authority superior to Scripture (for according to this theory we know far more doctrinal truth than the apostles), we earnestly protest against such a defense, which leaves the apostles chargeable with error (embracing the husk instead of the kernel), invalidates their testimony, and makes them unreliable guides. Under several of the propositions this feature will be duly examined; for the present we have only to say: the reason for such a lack of unity, of vital connection, of satisfactory apologetics, arises simply from ignoring a fact brought out vividly by Barnabas in his Epistle—viz., that the Abrahamic Covenant contained the formative principles, the nucleus of the Plan of Redemption; and that all future revelations is an unveiling, a developing, a preparation for the ultimate fulfillment of that covenant, and of the kingdom incorporated in the predictions and promises relating to that covenant. The legitimate outgrowth is alone to be received as the promised kingdom, without human addition in the way of defining and explaining. In this way only can we preserve the simplicity and harmony of Scripture, find ourselves in unison with the early preaching of this kingdom, and consistently, without detracting from the apostles and their immediate followers, defend the Divine record against the shafts of unbelievers.

The multiplicity and utter inconsistency of prevailing interpretations of the kingdom; the complete failure to reconcile such meanings with the preaching of the apostles; the unfortunate concessions made by able theologians to the Strauss and Bauer school on the subject of the kingdom; the impossibility of preserving the authority and unity of the apostolic teaching from the modern standpoint of the kingdom; the honest desire to obtain, if possible, the truth—these and other considerations led the writer to repeatedly consider, for many years, the Divine Revelation (in connection with the history of man) with special reference to this subject, until he was forced, by the vast array of authority and the satisfactory unity of teaching and of purpose which it presented, not only to discard the modern definitions as untrustworthy, but to accept of the old view of the kingdom as the one clearly taught by the prophets, Jesus, the disciples, the apostles, the apostolic fathers, and their immediate successors. In a course of reading and study it has been constantly kept in view, and the results, after a laborious comparison of Scripture, are now laid before the reader. This work is far from being exhaustive. Here are only presented the outlines of that which some other mind may mould into a more attractive and comprehensive form. Owing to providences which prevented the writer from actively prosecuting the ministry, he was directed to a course of study which influenced him years ago to draw up a draft of the present work. The need of such an one was then impressed, and this impression has been deepened by a varied and close observation. Yet, feeling the necessity of caution, it was held in abeyance to allow renewed reflection and investigation, until finally a sense of duty has impelled him to publish it as now given. If it possesses no other merit than that of presenting in a compact and logical form the Millenarian views of the ancient and modern believers, and in paving the way for a more strict and consistent interpretation of the kingdom, this itself would already be sufficient justification for its publication. The work, aside from its main leading idea, contains a mass of information on a variety of subjects and texts which may prove interesting, if not valuable, in suggestions to others. The author is not desirous to play the Diogenes, evincing, under the garb of humility and pretended low opinion of self, the utmost vainglory; or to enact the Alexander, showing, through an ardent desire for praise, a strong ambition for honors. A due medium, involving self-respect and a sincere desire to secure the approval of good men, is the most desirable, and also the most consistent with modesty. He therefore concluded, that no one could justly suspect his honesty of purpose, integrity, and desire to promote the truth, if he would publish his thoughts in the form herein given, even if he went to the length—impelled by what he regarded as truth—of giving the decided opinion, with reasons attached, that the views so universally promulgated respecting the kingdom of God are radically wrong, derogatory to the Plan of Redemption, opposed to the honor of the Messiah, and a remnant, remarkably preserved, of Alexandrian, monkish, and popish interpretation. Not that the writer claims entire freedom from error himself. Imperfection and a liability to err are, more or less, the condition of all human writings, even of the most well intended. Therefore, while, in illustrating or defending my own views, the opinions of others may be brought into review, it is far from me to assert that in some things, either through inadvertency, or ignorance, or prejudice, the author may not be ultimately found to be in error. Seeing that this is our own common lot, it would be unwise to approach each other’s works with any other than candid eyes and charitable hearts; so that, while we may feel to regret what appears to us a mistake, we may at the same time duly acknowledge the truth which is given. It may be proper to add in this connection, lest the spirit and motive be misinterpreted, that in the course of the work the names of authors are necessarily presented whose views are antagonistic to those here advocated. As it would have required considerable space to insert in each instance the respect and high regard the author has for them, although they thus differ from him, he may be allowed, once for all, to say that, while compelled to dissent from them, he nevertheless esteems them none the less as believers in Christ. Honestly impelled to differences, and, in justice to our subject, to criticize the views of eminent men, we still gratefully acknowledge ourselves largely indebted to many of them for valuable information, instruction, and suggestions. We have no desire to reproach them, or, in imitation of some of them in reference to ourselves, to call their integrity, or piety, or orthodoxy into question. We may even indulge the hope that this work may elicit renewed reflection, study, and discussion, leading to the removal of the evident weakness and contradictory statements of the prevailing Church view. Its publication may, we trust, be provocative of good, sustaining as it does the humble position of a forerunner of the truth, or the relationship of being merely suggestive, and thus opening the way for a more severe and critical examination of a doctrine which has been too much taken for granted. Defective as our works are in some respects, yet gifted minds have asserted, with charity and truth, that no mental toil, no laborious research, no earnestness of effort to interpret the Scriptures, however deficient in part or whole, should be undervalued, or scouted, or denounced, because all such may either present some truth which may serve to elucidate others, or produce thoughts that may be suggestive to others in introducing true knowledge. We too often overlook even our indebtedness to opposers of our opinions and belief. What Julius Müller says should influence us not only to attempt to labor ourselves, but to tolerate the efforts of others: “Our attempts to exhibit the truth in its entirety and connection are only like the prattle of children, compared with that clear knowledge which awaits us; but woe would it be to us if, because we cannot have the perfect, we should cease to apply to the imperfect, in all truthfulness and honor, our strength and toil” (quoted by Auberlen, Div. Rev., p. 415). This work is written under the impression, deepened by the testimony of able scholars, that the love of truth is one of the fundamental principles given to us by Christianity, and revived by the spirit of Protestantism and Science. Ignorance, fanaticism, party prejudice, etc. may indeed at times have obscured it, but intelligent piety has constantly restored it. Under its influence every inquiry after the truth, if conducted with reverence to the Word, without animosity, and in meekness, even if unsuccessful in its full attainment, is regarded by the truly learned and wise with charity, without an impugning of motives, or questioning of the religious standpoint of the searcher. This leads of course, to the position, that the credit we desire to be awarded to ourselves for presenting what we conceive to be truth, should be likewise extended to others. And if others claim, that they are not to decline the responsibility of holding forth the whole truth from our apprehension of consequences; that they are not to disguise or withdraw it through fear of giving offense, of losing reputation and support—we justly claim the same privilege. More than this: we can say with a distinguished theologian, who, contrasting the labors of more recent theologians with those of the older, and pointing out how the Old Testament is beginning to be appreciated in its relations to the New Testament, and the future—how the historical and doctrinal features of the primitive Church are more distinctly developed, how the place of the Church in its relation to the kingdom of God is more fully recognized—adds, that these are only “the beginnings of a work in which it is a pleasure and joy to have any share.”

This pleasure, however, is materially affected by one feature, the natural result of human infirmity. Uprightness demands that we follow the truth wherever it may lead, regardless of results, keeping in mind the remark of Canstein (Lange, Com., vol. 1, p. 516), “Straightforwardness is best. When we seek to make the truth bend, it usually breaks.” The doctrine discussed in the following pages being within the field of controversy, and the subject of varied interpretation, it will become in its turn, owing to its antagonism to the prevailing theology, the legitimate subject of criticism. Of this we do not complain, but rather commend the fact. “History repeats itself,” and in such a repetition we do not flatter ourselves to escape the usual fate of our predecessors in authorship. Indeed, we already have had sad foretastes of the same, confirming the teaching of Scripture, and corroborating the experience of good men, that no exercise of wisdom, caution, and prudence will be able wholly to avert the evil tongues and pens of others. Some men seem to be constitutionally constituted to be “heresy-hunters,” and imbibe largely the spirit of Osiander of Tübingen, who (Dorner’s Hist. Prot. Theol., p. 185, note) discovered in Arndt’s writings Popery, Monkery, Enthusiasm, Pelagianism, Calvinism, Schwenckfeldianism, Flacianism, and Wegelianism. Arndt survived the attack and still gloriously lives in the esteem of true Christian freedom, while his opponent is almost forgotten. This random illustration is taken from a vast multitude familiar to every scholar, and serves to indicate a weakness naturally inherent in some men, and who, perhaps, are scarcely answerable for its unfortunate display. Truth itself, however, requires no such picking of flaws, no harshness of language, no personality of attack, no bigoted and selfish support. She loves to hide herself in meekness, humility, and love, while the graces of the spirit surround and accompany her. The rude grasp, the rough touch even, is sure to mar the neat foldings and to spoil the downy softness and shining luster of her garments. That this work will bring upon the author bitter and unrelenting abuse is almost inevitable, presenting as it does unpalatable truths to a proud humanity. How can this be otherwise, when even the institution of the Lord’s Supper, intended as a bond of union and love, has been made the subject of uncharitable discord, violent abuse, and miserable hatred between professed believers. While we trust that the spirit which actuated many of the eucharistic controversies may never again arise, we are only too sensible, from treatment already experienced, that human nature remains the same. If the amiable Melanchthon did not escape, but most earnestly wished to be delivered from the rabies theologorum, how can others be safe? Even the Master himself was and is attacked, and the disciple is not above his Master. The virulence occasionally received from some quarters reminds one of the utterances of older controversialists, such as Henry VIII.’s work, Luther’s reply, and More’s rejoinder. Perhaps, like St. Austin and others, they regard such a manifestation of spirit as perfectly legitimate, desirable, and honorable. We do not quarrel with those who have inherited a taste for “bitter herbs.” Expressing ourselves candidly and fairly toward our opponents, we dare not return the epithets so liberally bestowed upon us. Two reasons prevent us: the first is, that dealing as we do “with the testimony of Jesus, which is the spirit of prophecy,” entering the sacred province of Scripture with the words of God constantly flowing from our pen, portraying the holy utterances of the Most High, it ill becomes us, when thus writing of the precious things pertaining to redemption, the kingdom of the Great King, and the ultimate glory of God, to mingle with it the painful evidences of human passion. The second is, dealing with a subject which, in the writer’s opinion, has been misapprehended by talented men, it is amply sufficient, for the elucidation and confirmation of the truth, to point out defects and exhibit statements in opposition without defaming the character or standing of any one. The latter procedure is worthy alone of a groveling jesuitical casuistry. Our names (Millenarian) have been linked with Cerinthus, heresy, etc., which is only imitating the amiable example of the Jesuit Theophilus Raynaud, who was noted for coupling his adversaries with some odious name to render them, if possible, contemptible by the comparison. It is the same trick resorted to by some Jews to wound Christ, and can only have weight with the unreflecting. To hold up the faults of opinion in others, for the sake of contrasting, explaining, and enforcing the truth, is allowable to all; especially when they are published, and thus become a sort of common property, or at least challenge the notice of others; but to hold up a man’s faults simply to make him odious is a despicable business. As Fuller (Eccl. Hist., Book X., p. 27) has wisely said: “What a monster might be made out of the best beauties in the world, if a limner should leave what is lovely and only collect into one picture what he findeth amiss in them! I know that there be white teeth in the blackest blackamoor, and a black bill in the whitest swan. Worst men have something to be commended; best men, something in them to be condemned. Only to insist on men’s faults, to render them odious, is no ingenious (sic) employment,” etc. We doubt not the ultimate fulfillment of Isaiah 66:5 in the case of many who have been thus defamed: “Hear the word of the Lord, ye that tremble at His word; your brethren that hated you, that cast you out for my name’s sake, said, Let the Lord be glorified: but He shall appear to your joy, and they shall be ashamed.” This passage suggests that a mistaken zeal for God’s glory may often be the leading motive of controversial bitterness—that our “brethren” may, through such overzeal, be its willing instruments. This, alas, embitters authorship on controverted questions. The opposition and obloquy consequent to and connected with such a discussion as follows while duly anticipated, as a heritage of the studious sons of the Church (the more marked their labors, the greater the abuse), would be less painful if it came only from infidels or the enemies of the truth, but much of it comes through those from whom, in view of a common faith and hope, we expect different treatment—at least forbearance if not charity. Acknowledging the respectful and Christian manner in which we are spoken of by a number of our opponents, yet the simple fact is, that if any one dares to arise and call into question the correctness of popular views and propose another, one too in strict accordance with the early teaching of the Church, his motives are assailed, his piety is doubted, his character is privately and publicly traduced, his learning and ability are lowered, his position is accorded a scornful and degrading pity, by persons who deem themselves set up for the defense of the truth. This plainness of speech the reader will pardon when he is assured that the writer, for the sake of the opinions set forth in this work, has suffered all this from the hands of “brethren,” who, by such efforts, reproaches, innuendoes, etc, have sought to lessen his influence and retard his preferment. Precisely as the learned Mede and hundreds of others have experienced. We here enter our protest, that truth is never benefited by such conduct, and that Christianity in its most rudimentary form forbids such treatment. But in justice to the really intelligent class of our opponents, we must say that such dealings toward us do not come from the truly learned opposer—for among such the writer has the pleasure of numbering valued friends. One feature of this work will bring upon us the censure of some—viz., the candid concessions made to unbelievers who attack the Scriptures, and the acceptance of the principle of interpretation (i.e., the grammatical sense), the views entertained respecting the kingdom by John the Baptist, disciples, and early church, etc., to which the writer is forced by justice, love for the truth, and the decided, overwhelming proof presented in behalf of the same. It must be acknowledged that many facts pertaining to the kingdom, as covenanted, predicted, and preached, are either entirely ignored or most imperfectly (inconsistently) explained by Christian Apologists. But these very concessions form for us a means of logical strength, of consonant unity, of accordance with Scripture and history, that, meeting unbelief fairly and honestly upon its own ground, furnish us with the proper weapons for defending the integrity of the Word and the reputation of the first preachers of “the gospel of the kingdom,” bringing a continued verification of the Divine utterance, that “a man’s foes shall be they of his own household.” Of course, we expect no special favor from gross Infidels, Spiritualists, Mystics, Free Religionists, and a variety of others, whose basis necessarily leads to opposition and whose unbelief is frankly criticized. Yet even such have dealt far more justly toward us, owing to our honest conceptions of historical facts, than members who were united with us in the same church. We may suitably close this section by again referring to that noble characteristic of candor which should, above all, mark our criticism of doctrine. We select as an apt illustration of our meaning the honorable example of Professor Bush. Although in his writings an opposer of Millenarianism, he endeavors to conceal no facts, however adverse to himself, but freely gives them, being too much of a scholar to be unacquainted with them, and too much of a gentleman and Christian either to ignore, or to despise, or to deny them. Thus, e.g., he fully admits the universality of our doctrine in the first three centuries and eloquently says: “We are well aware of the imposing array of venerable names by which it (Chiliasm) is surrounded, as if it were the bed of Solomon guarded by threescore valiant men of Israel, all holding swords, and expert in war.” Unable to receive our doctrine, he still does justice to that noble list of martyrs, confessors, writers, theologians, missionaries, and others, who have held it, and finds in them the redeeming qualities of Christian integrity, faith, love, and holiness.

It is a fact, lamented by some of our ablest divines, that there must be something radically wrong in our prevailing interpretation of the Bible, which allows such a diversity of antagonistic exegesis and doctrine, and by which the truth is weakened and humbled, so that Revelation itself, by its means, becomes the object of Rationalistic and Infidel ridicule and attack, and is even sorely wounded in the house of its friends by its stumbling, conceding, but well-meaning apologetic defenders. To indicate this feeling, which prevails to a considerable extent, Dr. Auberlen (Div. Rev., p. 387) quotes Rothe as saying respecting the defects of exegesis: “Our key does not open—the right key is lost; and till we are put in possession of it again, our exposition will never succeed. The system of biblical ideas is not that of our schools; and so long as we attempt exegesis without it, the Bible will remain a half-closed book. We must enter upon it with other conceptions than those which we have been accustomed to think the only possible ones; and whatever these may be, this one thing at least is certain, from the whole tenor of the melody of Scripture in its natural fulness, that they must be more realistic and massive.” This is a sad confession after the voluminous labors of centuries, and yet true as it is sorrowful. We may be allowed to suggest, that the only way in which this key can be obtained is to return to the principles of interpretation adopted and prevailing in the very early history of the Christian Church, by which, if consistently carried out, the kingdom of God in its “realistic and massive” form appears as the reliable interpreter of the Word. In other words, we have no suitable key to unlock Revelation if we do not seize that provided for us in the revealed Will of God respecting the ultimate end that He has in view in the plan of redemption and the history of the world. A way is only known when the beginning and terminus are considered; a human plan can only be properly appreciated when the results of it are fully weighed: so with God’s way and God’s plan, it can only be fully known when the end intended is duly regarded. How to do this will be contained in some of the following propositions. That it will be accomplished we doubt not, and we are encouraged to labor on when such men as Dr. Dorner (p. 4, Introd., vol. 2, Hist. of Prot. Theol.), expressing the sentiments of many others, says: “There can be no doubt that Holy Scripture contains a rich abundance of truths and views, which have yet to he expounded and made the common possession of the Church,” and adds, that this will be done as the necessity of the Church requires. This, however, cannot be accomplished without long and laborious study of the Scriptures, diligent comparison of them, and inflexible abiding within the limits of their plain, grammatical teaching. We have no sympathy with that flippant, unargumentative, high-sounding, but unscriptural mode of presenting theological questions, so prevalent at the present day, by which the merest tyro of a student endeavors to elevate himself, as a teacher, above men who have been trained by grave and extended reflection, and which manifests itself by despising the teachings of the Apostolic Fathers and of the noble men of the Church, and enforces its views by an applauding of modern views and modern theories as evidences of progression in truth. The dignity of religion, the steadfastness of faith, and the reliability of the discovery of truth, must suffer by such a style, which lacks the strength imparted by a scriptural basis—a “thus saith the Lord”—being built upon the deductions of reason, with, perhaps, here and there a scripture passage thrown in by way of ornament. Give us men, who, instead of following their own fancies, or binding their faith to human utterances, availing themselves of preceding knowledge, patiently, thoughtfully, and reverently go to the very roots of questions, and in things revealed by God determinately reject everything inconsistent with such a revelation. We know that such a course demands courage and study, but in every instance when exhibited by published labors, it will command, if not the entire assent, the respect of the truly learned; for the latter, from experience, can appreciate, at least, the toil in producing such a work. Give us such men, and then we can hope to make advancement in Christian knowledge, in harmonizing the difficulties besetting theology, and in widening the domain of thought, faith, and hope. “What we want is solidity, and that, in theology, is alone attainable by having underneath as a foundation to build on the pure declarations of God. What God says is true, what man says may be true; and the truthfulness of the latter can be ascertained, its certainty demonstrated, by comparing it with that which God has declared. If the comparison is favorable, let us accept of it; if unfavorable, then let us have the Christian manhood to reject it, no matter under whose name, patronage, or auspices it is given. Rendering the regard due to the writings of others, it does not follow that we must elevate them to the position of competitors of, or peers with, the Divine utterances. Such a test the author solicits from the reader, bringing to the consideration of the subject an impartial judgment, and weighing its value and authority in the scripture balance and not in human scales. Every sincere lover of the truth, even should his labor be rejected in part or whole, must feel honored by the institution of such a comparison.

It has, however, been the fate of some authors to be so far in advance of their contemporaries that, appreciated only by the few discerning or candid, it has required time, or the necessity of the Church, or the endorsements of a line of students to give importance and weight to their statements. While the deepest thinkers freely admit that new and valuable contributions to theology are reasonably to be anticipated, that such are absolutely required at the present juncture, and that such can only be found in the rich resources of the Word, yet it is remarkable that a contribution thus given will, especially in the hands of those whose minds are controlled by human traditions and by an exalting of Church authority above that of the Scriptures, be rejected and anathematized on the ground of its being in opposition to their preconceived and favorite formula of doctrine. Others, through indifference or an indisposition to examination, will pass it by with, probably, a momentary interest. Others again, the few tried friends of intellectual and theological effort, will give it a fair, frank, and sincere reception, and form a candid estimate of its value based exclusively upon its correspondence with the Holy Scriptures. The latter occupy the real student position—one that Dorner has aptly characterized as of “individual freedom, that indispensable medium for all genuine appropriation of evangelical truth”—a freedom only limited by Revelation. Without intending an imitation of such great writers as Bacon and others, who declared that they wrote for “posterity,” and that it would require time to “ripen” their views so as to cause their due appreciation, yet such is the subject-matter of this work, so beset and resisted by the torrent of opposing doctrine, so circumscribed by the entrenched prevailing dogmas, so unpalatable to the licentiousness of the increasing free-thinking, so unwelcomed to a proud and self-satisfied reason, that we are justly apprehensive of an overwhelming opposition to the following propositions. In this belief we are fortified by the predictions of the Word, which unmistakably teach that they will find but little acceptance with the world, and even with the Church at large, and that they will only be pondered and received by the thoughtful few. In this period of prosperity, of sanguine hope of continued and ever-increasing peace and happiness, the minds and hearts of the multitude will be closed against all appeal, all instruction. It is only when the dreadful storm of persecution and death, alluded to in several propositions, shall, when excited and marshaled by the elements and forces now at work, burst with fearful violence upon the Church, and beat with pitiless vehemence upon the heads of true, unflinching believers in Christ, that this work will find a cordial response, a hearty welcome in the breasts of the faithful. Time with its startling and terrible events will justify this publication. When the dreams of fallible man, now so universally held as the prophetic announcements of God, are swept away by stern reality; when, instead of the fondly anticipated blessedness and glory to be brought about by existing agencies, the blood of man shall again stain and steep the soil of earth with its precious crimson, then will the doctrine of the kingdom, as here taught, be regarded worthy of the highest consideration, and then will it also become a solace, hope, and joy under tribulation. But to remove the suspicion of arrogance or pride in making so strong an assertion, we may be allowed to say, that such a future estimation is not based on literary or theological merits or attainments, but solely upon a strict adhesion to and firm belief in the infallible Word of God as herein delineated under the guidance of a legitimate rule of interpretation, by which the Divine purposes relating to the Church and world are plainly and distinctly taught. The possessions of God, even the most costly, are often given to mere children, and denied to the wise and noble. The Magi, although babes in knowledge compared with the Pharisees, came nearer to the truth than those who supposed themselves to be specially set up for its advocates. Numerous examples attest the same and reveal the feature, that just in proportion as a man, learned or unlearned, receives and endorses the declarations of God, to the same extent will his writings have an abiding value. Especially is this true concerning the things pertaining to the future—that region, those ages known only to the Eternal, and utterly impenetrable to mere mortal vision. Hence, the writer consistently claims that his labors will not be in vain; that they will at least some day be esteemed in the degree that they sustain to the Bible. We firmly hold to the opinion, confirmed by the providences of God, that the necessity has arisen for a renewal of the early Church doctrine respecting the kingdom. If the millennial age, as conceded by a host of antagonistic writers, is near at hand, and if the kingdom in that age is such as herein portrayed, then is the kingdom itself not very distant, and then too ought we reasonably to expect—in view of its peculiar nature, prominence, aims, etc., especially of its immediate tremendous and frightful antecedent preparations, and of its becoming a net and snare for the unbelieving and wicked—that before its appearance God will raise up instruments—even if weak Jonahs—who will so distinctly announce the order of events, so vividly represent the nature of the kingdom, point out its manner of manifestation, give a precise understanding of the Church’s actual relationship to the world and this kingdom, that the Church will be prepared to endure the awful scenes awaiting her, and that the saints, called to suffer the loss of life, may, in the thus revealed will of God, find encouragement and comfort instead of disappointment and despair. With the hope of being thus honored with others as an instrument in upholding the faith of God’s dear children in the darkest period of the Church’s history, one will sadly but cheerfully endure the censures of mistaken zeal and bigotry, and give his days and years of wearisome labor as an inspiring sacrifice of love.

The doctrine herein advocated, because of its being so directly opposed to the current theology, and perhaps new in form to some readers, must not be regarded in the light of a novelty. It is, as we shall show, far older than the Christian Church, and was ably advocated by the founders and immediate supporters of that Church. It is admitted by all scholars, that the Apostolic Fathers and many of their successors endorsed it, and that since their time eminent and pious men have taught it, and that today it is embraced in the faith of some in the various denominations of the Church. We therefore are not open to the charge of introducing a “modern novelty.” Again: men of pretensions, without perceiving the logical result of its once being universally held by the early Church, may deride this early view of the kingdom and stigmatize it as a return to “Jewish forms.” But persons of reflection, seeing how largely it is interwoven with the very life, prosperity, and perpetuity of the Church in its earliest period, and perceiving how deeply we are indebted to “Jewish forms,” even if unable to accept of its teachings, regard its faith with respect. Indeed, it is difficult to apprehend how any one can scorn that which inspired a hope that supported and strengthened the ancient steadfast witnesses for the truth, the very pillars of the Church in their sufferings, the dying martyrs at the stake, on the cross, or in the circus. Cut off the believers of this very kingdom as they existed and testified in the first, second, and third centuries, and where would be the Church? The really intelligent comprehend this, feel its force, realize their indebtedness to such believers for the perpetuation of gospel truth, and hence from such we anticipate no censure, couched in derision, in advocating what was once almost, if not entirely, universal in the Church. They are ready to acknowledge how, instead of its being a novelty and being held by weak and unreliable men, it interpenetrated the most significant and remarkable era, and how widely it was inculcated by the very teachers to whom the Church owes, under God, its growth and extension.

Some, probably, may object to the quotations as excessive or pedantic, but the reader will allow me thus to express my gratitude to and respect for others; thus to avoid the charges of misquoting or misstating writers (from which he has unjustly suffered); hence the author, book, and page are adduced to facilitate reference and indicate an intended fairness in argument, thus to aid those who are disposed to examine the affirmations in the following propositions; to show how many great and earnest thinkers have given this subject, or parts of it, their earnest attention; to evince my indebtedness to others, and avoid the appearance of so many writers of the present day, who, while under great obligations to others for valuable material, give no sign of a just recognition; to imitate the conduct of those who go forth to meet the storms of the sea, taking in a quantity of ballast to keep the bark steady among the currents and winds; to emulate the practice of writers of conceded merit, impressed by the fact tersely stated by D’Israeli (Curios. of Lit., vol. 2, p. 416), that “those who never quote, in return are seldom quoted;” to present a sense of delicacy by avoiding “the odium of singularity of opinion,” adding weight and authority to what otherwise might be regarded as doubtful; and, lastly, to avoid even by implication the application of the simile of Swift in The Battle of the Books—viz., of being like the spider weaving his flimsy nets out of his own bowels, instead of being like the bee passing over the field of nature and gathering its sweets from every flower to enrich its hive. We may be allowed to add: like the bee, however, we may justly claim, if nothing more, the industry and skill requisite in the gathering of the wax, the honey, and the building of the cells. Indeed, such is our infirmity, that we all are more or less influenced by the authority of names, and in the reading of a work chiefly composed of controverted questions given in an argumentative form, we reasonably expect an array of advocates on both sides, which imparts confidence that the author has bestowed some attention to the subject, and makes his labor, in consequence, the more valuable as an expression of opinion or a book of reference. At the same time, important as it is to the student to know and trace opinions, we are not influenced, either by their commonplaceness, axiomatic nature, or remoteness in time, to assert, as Glanvil (Lecky, Hist. of Rat., vol. 1, p. 132, note) sarcastically charged the scholars of his day, on the authority of Beza, that women have no beards, and on that of Augustine, that peace is a blessing, or to believe that common pebbles must be rare because they come from the Indies.

Finally, the form of propositions adopted avoids repetition and insures easy reference. It also gives distinctness to the numerous subjects so intimately connected with the kingdom, and it enabled the writer to abridge what otherwise would have required considerable enlargement. The design kept in view has been to give the greatest amount of information within the smallest space, resisting the temptation, often presented, of extending some salient point. The propositions, separately treated, are to be examined and criticized in the light which each one sustains in its connection with the whole. It is but a low polemical trick to detach one from the rest without indicating its relationship to others, and upon such a detachment frame a charge of error. It does not require much cunning or skill to wrest the words of any author from their connection, to misrepresent their meaning, and to hold them up to undeserved reproach. Willing to have any fault or error pointed out, it must, to give it adequate force, be done not only with a consideration of the manner and relation in which it is set forth, but also of the scriptural arguments, if any, which profess to sustain it. Otherwise, we take refuge in what Zeisius (Lange, Com., vol. 1, p. 496) says: “If the words of Christ, who was eternal Wisdom and Truth, were perverted, why should we wonder that His servants and children suffer from similar misrepresentations.”

GEORGE N.H. PETERS

SPRINGFIELD, OHIO, 1883.

Prop. 1. The kingdom of God is a subject of vital importance

The Scriptures cannot be rightly comprehended without a due knowledge of this kingdom. It is a fact, attested by a multitude of works, and constantly presented in all phases of Biblical literature, that the doctrine respecting the kingdom has materially affected the judgments of men concerning the canonical authority, the credibility, inspiration, and the meaning of the writings contained in the Bible. If in error here, it will inevitably manifest itself, e.g., in exegesis and criticism. This feature has been noticed by various writers, and, however explained, the views entertained on this subject are admitted to greatly modify the reception, the interpretation, and the doctrinal teaching of the Word.

To illustrate: Olshausen, Pref. to Com., attributes Luther’s remarks and hesitancy concerning the Apocalypse to a preconceived opinion of the kingdom, and to his not “thoroughly apprehending the doctrine of God’s kingdom upon earth.” Numerous examples will be given as we proceed. It is gratifying that recent writers begin to appreciate the leading doctrine of the kingdom. While some are wrong in not more accurately distinguishing between the Divine Sovereignty (Props. 80 and 81) and the covenanted kingdom (Prop. 49, etc.), yet, as the Bible, they correctly make the kingdom of God the central topic around which all other doctrines logically arrange themselves. Correctly apprehending the kingdom of God as the guiding idea, Oosterzee (Ch. Dog., vol. i. p. 65) justly observes: “The dogmatic theology which understands its vocation will be neither more nor less than a theology of the kingdom in all the force of the word.” He aptly remarks (p. 168): “The idea of the kingdom of God is the golden thread which runs through all; and of this kingdom the Bible is the document;” and quotes Nitzsch: “The Word of God is the testimony of His kingdom, in the form of a history and doctrine explained and continued by personal organs.” Many others, however they may treat it, designate it as Augustine (The City of God), a fundamental thought or idea.

Obs. 1. Its importance may be estimated by considering the following particulars: 1. The kingdom is the object designed by the oath-bound covenant (Prop. 49). 2. It is the great theme, the burden of prophecy (Props. 33–35, etc). 3. It is a subject which embraces a larger proportion of Revelation than all other subjects combined; thus indicating the estimation in which it is held by God. Dr. Pye Smith, Bickersteth, and others have well observed and commented on this peculiarity—viz., that inspired writers say more respecting the kingdom of Christ than they do concerning all other things treated or discussed in the Word. 4. It was the leading subject of the preaching of John the Baptist, Christ, the disciples and apostles (Props. 38–74). 5. It was a cherished subject of preaching in the primitive Church (Props. 75–77). 6. It is the foundation of a correct scriptural preaching, for the Gospel itself is “the gospel of the kingdom.” 7. To promote its establishment Jesus appears, suffers, and dies (Props. 50, 181), and to manifest it He will come again (Props. 66, 68, 130, etc.). 8. Jesus Christ Himself, must be deeply interested in it, since it is a distinguishing blessing and honor given to Him by the Father (Prop. 84), and belongs to Him as His inheritance (Props. 82, 116, etc.). 9. We are invited, as the most precious of privileges, to inherit this kingdom (Prop. 96). 10. It is the constantly presented object of faith and hope, which should influence us to prayer, duty, and watchfulness. 11. It is the result of the preparatory dispensations, enabling us to appreciate the means employed to attain this end. 12. It embraces within itself perfect completed redemption; for in it all the promises of God will be verified and realized. 13. It exhibits in an outward form the pleasure of the Divine will in the salvation of the race and the deliverance of creation (Props. 149, 145, etc.). 14. It brings the Divine utterances into unity of design (Props. 174, 175), exhibits manifested unity (Prop. 173), and vindicates the inspiration of Holy Writ (Prop. 182), including the Apocalypse (Prop. 176). 15. It enforces not only the humanity (Props. 82, 89) of Christ, but also His Divinity (Props. 85 and 183), with the strongest reasoning. 16. It exhibits to us the majesty and glory of Jesus, “The Christ,” as Theocratic King (Props. 88, 89, 132, 184, etc.), and the preeminent position of “the first-born” who are co-heirs with Him (Props. 118, 119, 127, etc.). All these, as well as other related points, will be fully discussed in the following pages. A sufficiency is briefly stated, that the reader may not fail to see how significant must be a proper comprehension of this subject.

We are prepared, from such considerations, to appreciate the remark attributed by Lange (Com., vol. 1, p. 254) to Starke: “The kingdom of heaven must form the central point of all theological learning.” Van Oosterzee (Theol. of the N.T., p. 69) calls it the foundation thought, and, after giving the doctrine of the kingdom its proper position in the teaching of Jesus (saying, “that the idea of the kingdom of God is fundamental in the theology of Christ,”) remarks: “Already Hess has furnished a treatise on the doctrine of the kingdom of God, in which he shows how prominent a place this idea occupies in Holy Scripture, especially in the teaching of the Lord. It is surprising therefore that Schmid, in the work cited, assigns to it the third place in his treatment of the doctrine of Jesus. Much better Neander, who, in his life of Jesus, derives a ‘whole system of truths’ from the parables of the kingdom of God.” Let us add, however, that even Schmid does ample justice in acknowledging its importance, when (e.g., Bib. Theol. N.T., p. 243) he calls it, the groundwork of His (Christ’s) teaching.

Such testimony could be multiplied. It is gratifying to find numerous recent writers of eminence (as e.g. Delitzsch, Auberlen, Kurtz, Bonar, etc.) who emphatically declare that the most important subject for careful consideration, and the one, too, that will most serve to explain the plan of salvation, is that contained so prominently in the preaching of Christ, viz., that of the kingdom. We conclude in the words of one of the most recent, Thompson (Theol. of Christ, p. 19): “The whole circle of doctrines taught by Christ revolves about this central point, that he represented to men the kingdom of God;” or to recall Oosterzee (Ch. Dog., vol. 1, p. 169): “The central thought is contained in the idea of the kingdom of God.” Dr. Kling (Herzog’s Ency., Art. “Kingdom of God”) pertinently says: “The idea of the kingdom of God is the central idea of the entire economy of revelation; the kingdom of God is the purpose of all heavenly revelation and preparations, and therefore the moving principle of Divine works, guidance, and institutions of the Old and New Testament, the law and the gospel, and even of creation and promise from the beginning on.”

Obs. 2. It is significant to the thoughtful student—a fulfillment of prophecy—that the idea of a distinctive Divine kingdom related to Christ and this earth, a kingdom which decidedly holds the foremost place in the teaching of Jesus, should be made, both (with few exceptions) in theology and the confessions of the Church, to come down from its first position in the Bible and occupy, when alluded to, a very subordinate one. In hundreds of books, where it reasonably ought to be conspicuous, a few references of a somewhat mystical and unsatisfactory nature, or a brief endorsement of the old monkish view that it applies to the Church, dismisses the entire subject; while inferior subjects have long chapters and even volumes in their interest. There is, to the reflecting mind, something radically wrong in such a change of position, and the wider the departure from the scriptural basis the more defective does it become. Any effort, as here made, to restore the doctrine of the kingdom to its true and paramount Biblical station should at least solicit attention.